John von Neumann: A Strange Kind of Bird

What his career can teach us about the nature of scientific creativity.

Last week, I finished a new biography that I’ve been waiting on for months. Eagerly waiting for a book to be released is not something I make a habit of. But this was different: this book was about the great Johnny von Neumann.

On top of von Neumann’s wide-ranging excellence being fun to read about, the way he made many of his contributions, particularly in fields completely dissimilar to his native field of mathematics, provides insight into the kinds of creativity and collaboration we should be finding ways to incentivize in the research community.

Unlike someone like Dirac, whose major contributions felt to many contemporaries as if he were conjuring mathematical laws of nature out of the sky, von Neumann’s process seems to be something that is much more replicable. While I have no hopes that one person can or should hope to replicate what he did, it is believable that many researchers, if properly encouraged to seek problems and collaborate in a way similar to von Neumann, could hope to replicate results as fantastic as his.

Many of von Neumann’s major contributions to fields like economics and computer architecture should not be characterized as strokes of genius from an out-of-this-world brain. Rather, his creation of game theory, the economic concept of utility being a number, and ‘von Neumann architectures’ in computing were more the byproducts of an excellent mathematician making expert use of the tools of his trade in approaching the problems of other fields.

In today’s piece, I’ll share just some of the many fantastic achievements of von Neumann’s career and reflect on what his career can teach us about the nature of creativity in an interdisciplinary context. This post is much less data-centric than previous Engineering Innovation posts; that is because I believe the stories below, combined with common sense, speak for themselves.

Most of the historical narrative in this post draws from Ananyo Bhattacharya’s wonderful new biography, The Man from the Future: The Visionary Life of John von Neumann, and the Privatdozent piece, The Unparalleled Genius of John von Neumann.

Enjoy! 1

John von Neumann is, by many accounts, the smartest man to have ever lived. Some, who are more casually interested in the history of science, are not aware of this because he did not make an individual, earth-shattering discovery that altered the way we see a field the way figures like Einstein or Gödel did—Einstein’s theories of relativity and Gödel’s incompleteness theorem.

But Johnny’s fingerprints are all over the creation of many fields that are even more important today than they were when he first contributed to them over 70 years ago. Not to mention, almost all of the early 20th century’s scientific greats held von Neumann in unbelievably high regard.

Jørgen Veisdal, who publishes the magnificent Privatdozent Substack, opens his famous piece on von Neumann with several such accounts.

”You know, Herb, Johnny can do calculations in his head ten times as fast as I can. And I can do them ten times as fast as you can, so you can see how impressive Johnny is” — Enrico Fermi (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1938)

“One had the impression of a perfect instrument whose gears were machined to mesh accurately to a thousandth of an inch.” — Eugene Wigner (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963)

“I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man” — Hans Bethe (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1967)

“There was a seminar for advanced students in Zürich that I was teaching and von Neumann was in the class. I came to a certain theorem, and I said it is not proved and it may be difficult. von Neumann didn’t say anything but after five minutes he raised his hand. When I called on him he went to the blackboard and proceeded to write down the proof. After that I was afraid of von Neumann” — George Pólya

Von Neumann was 20 at the time of that last story.

His mind was truly a marvel. And his brain’s inhuman capacity was not limited to the mathematical. A Princeton Professor of Byzantine History once said that he would only attend one of von Neumann’s famous parties if von Neumann promised not to bring up the subject of Byzantine history, because many thought the professor to be the world’s foremost expert on the subject, and he did not want anyone to know that that title might actually belong to von Neumann. It’s true that von Neumann’s eidetic memory gave him an advantage, but this type of comment about von Neumann was made by many experts.

His mind was a force, unheard of by even his other famous contemporaries. Mathematicians joked, “Most mathematicians prove what they can, von Neumann proves what he wants.”

Bhattacharya’s new biography of von Neumann was built around von Neumann’s ideas themselves and their legacies more so than strictly adhering to the timeline of von Neumann’s life. (I personally feel von Neumann would appreciate that his biographer made this stylistic choice.) And so the book progressed, detailing one ground-breaking intellectual journey to the next, from set theory to quantum mechanics to game theory to explosives to computer architecture.

‘Dabbling’ would be the wrong word to describe his wide-ranging contributions. He did not so much dabble as parachute in, make a major contribution to a field, and then move on to his next adventure, leaving others to work out details and expand on the implications of his usually ground-breaking work.

I thoroughly enjoyed hearing account after account of von Neumann’s life and process. But after I completed the book and was reflecting on what his life and wide-ranging and novel thinking could tell us about how to engineer more innovation, I became confused.

I was confused because I remembered that one time Freeman Dyson, a famous mathematician and younger contemporary of von Neumann, categorized great mathematicians in the following way:

Some mathematicians are birds, others are frogs. Birds fly high in the air and survey broad vistas of mathematics out to the far horizon. They delight in concepts that unify our thinking and bring together diverse problems from different parts of the landscape. Frogs live in the mud below and see only the flowers that grow nearby. They delight in the details of particular objects, and they solve problems one at a time. —Freeman Dyson

And this is an analogy I think about a lot. For many great researchers, the line between the two categories might be blurred, but each category seems to accurately describe the two major types of thinking that lead to great discoveries. Some great ideas result from the high-level thinking that connects disparate ideas and concepts; others result from making expert use of the tools of a trade to work out important details and specific questions that are all important in understanding the big questions in a field. As I finished reading, I could not stop thinking about this breakdown because in the same piece that Dyson introduces this breakdown, he uses von Neumann as the example of a PROTOTYPICAL FROG.

How could that be?! Freeman Dyson is surely not stupid. He was both incredibly intelligent and knew von Neumann. I turned this over and over in my mind for a week. How could a great mathematician who was very familiar with von Neumann characterize him as a frog when he contributed so impactfully to so many different fields? That felt, to me, like the stuff birds were made of. Was it not?

After a week, I feel I’ve come to a satisfactory conclusion. The truth, as is often the case, may simply be a matter of perspective. And the answer to this quandary, I believe, says a lot about how we can manufacture more ‘creativity’ in academia without making any single person any smarter.

(If anyone believes the line of reasoning is incorrect, please let me know. I believe one or two of my subscribers may have known Dyson personally.)

A Matter of Perspective

Dyson gave this comment at a meeting of the American Mathematical Society. And in calling von Neumann a frog, he likely was only referring to von Neumann’s work in the field of mathematics itself — from the point-of-view of a mathematician. Freeman Dyson, a mathematician who worked on physics problems, existed in worlds where von Neumann’s tricks were part of the standard toolkit. I am primarily educated in the fields von Neumann contributed to outside of math and physics. And that might be the difference that makes me see Johnny, with his major contributions to fields like economics and computer architecture, as being so bird-like.

In mathematics and quantum mechanics, von Neumann’s tricks, which he expertly used, were more or less a part of the standard toolkit and approach to problems. What often makes one mathematician great is an expert ability with even just one of these tools. Having the sharpest tool in the shed can count for a lot. Take Norbert Weiner as an example. Norbert Weiner was known for his mastery of Fourier Transforms and this mastery was vital to much of his work. Mastery of these types of tools was vital to many famous frogs. For von Neumann, one of his finest tools was the ability to formalize particular physical problems into mathematical logic. We see him do this time and time again throughout his biography in most of the fields in which he worked. This tool was, for him, a gift that kept on giving.

And, to a mathematician, what was impressive about that toolkit of von Neumann’s was both the sharpness of his tools and that he had several extremely sharp tools, not just one. But to a social scientist or contemporary computer engineer such as those who worked on the ENIAC, the true novelty was the tools themselves and his ability to make them work in a new field. Being able to formulate the problems of game theory or computer architecture with logic truly helped revolutionize those fields.

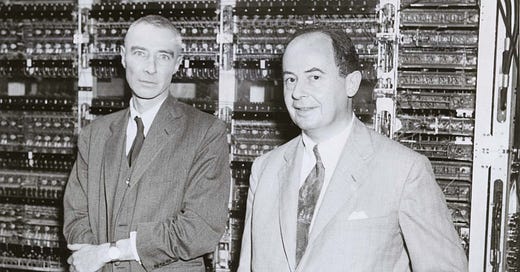

Take computing as an example. The ENIAC was, even to those who worked on it, something of a haphazard mess of vacuum tubes. Von Neumann’s team’s proposal for the EDVAC, and what came to be known as von Neumann architectures, reformulated this engineering problem in a way that was unbelievably clean and intuitive. And this allowed the field of computing to achieve new heights. These von Neumann architectures are still the most common architecture used in modern computers.

When it came to game theory, his ability to encode the problems of a field in mathematical form was even more pronounced. Not only did von Neumann’s mathematical theorem, minimax, enable the field to exist, but his work with Oscar Morganstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, was the first to start properly building on this mathematical foundation he laid. Their work was the first true formalization of many of these imprecise social science problems into what now is the rigorous field of social science known as game theory—likely the most rigorous social science. This field inspired many of the best economics and mathematics graduate students of the later 1900s to join its ranks and dedicate entire careers to solving specific problems within the field. To date, fifteen different game theorists have received Nobel Prizes in economics.

Von Neumann’s contributions to the fields of social science and computer architecture were at such a basic level that we can hardly imagine the fields today without them. The EDVAC report authored by him and several others, which laid out the von Neumann architecture for the first time, describes computers as we know them today.

It laid out the design of an electronic computer made up of only the following components:

A processing unit capable of arithmetic operations and with some basic storage functions

A control unit capable of holding and keeping track of instructions

Memory that stores instruction and other data

External, large-scale storage

Input and Output Mechanisms that allow users to feed in requests and receive outputs from the machine as a result of the requests.

And, as hard as it may be for many to imagine, the simplicity of this architecture was completely non-obvious at the time. Prior to this innovation, “program-controlled computers” existed, such as ENIAC at UPenn, which could only be programmed by manually setting switches and inserting new cables to route data. Visually, an outsider observing the programming of these computers did not look dissimilar to the work of a telephone switchboard operator. Programming as we know it came into being as a result of von Neumann architectures. In fact, as Bhattacharya notes in his book, von Neumann’s second wife, Klará, was one of the first modern computer programmers.

And, when it comes to social science, von Neumann did something possibly even more important than founding game theory. The concept of utility existing as a number was first formalized by von Neumann himself. The importance of this building block to modern economics cannot be overstated. Modern economics as a discipline would look extremely different without this key piece of knowledge.

Even Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner in economics and one of the co-founders of the field of behavioral economics, believes this contribution to be indispensable to the field. Many might think that Kahneman may see this mathematical contribution as less impressive than other economists because behavioral economics is, to some, a bit of a backlash against the mathematization of the social sciences. But they would be wrong. Kahneman has stated that this contribution by von Neumann is the most important theory in all of the social sciences.

Not bad for a mathematician.

If you also find it hard to believe that this concept was not in practice before von Neumann introduced it, then you’d be in the same boat as von Neumann himself when he first broached the subject. Oscar Morganstern, his economist co-author, told von Neumann that the orthodoxy in economics was that utility could not be measured numerically—it was measured by rank-ordering outcomes instead. When von Neumann heard this, he, along with Morganstern, quickly jotted down a theory with axioms proving how to do this. He then asked, “But didn’t anyone see that?”

Nobody had. Not before him.

Sometimes a frog, sometimes a bird

A non-exhaustive list of fields in which von Neumann made contributions can be found below. Admittedly, I only understand about half of his contributions. But I’ve done my best to report as many as possible below.

Set Theory and Logic

His succinct list of axioms resolved several paradoxes of set theory that existed before his work and contributed to what was later known as von Neumann-Bernays-Gödel set theory (NBG).

His work first introduced the notion of a class to set theory.

Operator Theory

Enabled the study of ring operators through the invention of what we now know as von Neumann algebras.

Ergodic Theory

Von Neumann’s mean ergodic theorem was seen as the first proper mathematical foundation for the statistical mechanics of liquids and gases. He published this finding in a series of two papers.

“If von Neumann had never done anything else, they would have been sufficient to guarantee him mathematical immortality.” — Paul Halmos (1958)

Quantum Mechanics

Von Neumann published a set of papers that helped establish a rigorous mathematical framework for quantum mechanics that are now known as the Dirac-von Neumann axioms. In these, he describes the states of physical systems using Hilbert space vectors and measurable qualities in a framework where unbounded hermitian operators act upon them.

Using this new framework, he also expounded on how the theory should be interpreted statistically.

Prior to von Neumann’s work, there was a relatively complete formal mathematical theory, but it was considered clumsy and hard to build on because of its reliance on **ill-defined mathematical objects which physicists spent much time debating.

Continuous Geometry

A field invented by von Neumann that was an analog to complex projective geometry where, instead of a dimension being some integer, it could be an element of the unit interval [0,1].

The top 5 areas, sandboxes which Freeman Dyson also played in, are areas where von Neumann may likely be considered a true frog. It was the sharpness and number of tools that enabled his contributions in these fields. The next five categories are where his more bird-like work was done. His ability to find ways to use the approaches of his own field to solve problems in others was an underrated tool of his in and of itself.

The Physics of Explosives

Von Neumann was pivotal in helping determine the answer to the surprisingly difficult problem of how to shape the charges for the atomic bomb. In addition, the decision to set the bomb off in mid-air and not upon impact was a result of von Neumann’s calculations.

Similar calculations done for the navy by von Neumann helped the US get so much more bang for their buck out of their explosives that the Germans believed the US had found some new, more potent kind of explosive. It was just von Neumann figuring out the optimal depth at which to set the bombs off.

Economics

In building a model of a basic economy, von Neumann’s expanding economy model, von Neumann was the first researcher to use a fixed-point theorem to solve a problem in the field of economics. This tool became a common feature of mathematical economics in the decades following.

As mentioned above, his minimax theorem along with his work with Oscar Morganstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, birthed the field of game theory.

As mentioned above, the von Neumann-Morganstern utility function established that individual preferences could exist on an interval scale and that individuals always prefer actions that maximize expected utility. Prior to this, economists rank-ordered actions based on utility but could not assign numbers to the entity.

Computer Architecture

His team invented the concept of von Neumann architectures covered more in-depth in the preceding section.

Other Computing

Von Neumann invented the merge-sort algorithm.

He is also responsible for first introducing the concept of stochastic computing—which, while groundbreaking, could not be implemented for another decade due to the limitations of computing at the time.

He invented Monte Carlo simulations along with his good friend Stanislaw Ulam.

He used the methods from his minimax and game theory work to help George Dantzig in his development of the field of linear programming.

Automata Theory

Von Neumann more or less invented the field of cellular automata by giving a mathematical rigor to the concept of self-replication. It was his work on early computers that inspired this work and the concept of automata still persists strongly in the field of computer science to this day.

In doing this work, he also predicted, in a basic sense, how DNA would likely replicate and function based on the concepts he was building on in the field of cellular automata. He, unsurprisingly, turned out to be right when Watson, Crick, Franklin, and Wilkins later made their discoveries.

Also, as a note, the noted independent researcher Stephen Wolfram is attempting to use the concepts of cellular automata to build a theory of everything and a new kind of physics-based on computation rather than mathematics—although his methods have grown much more complex.

Laying the groundwork for more Johnny’s

In a world where we seem to be discovering new fields less and less, these are the kinds of connections we should be re-engineering systems of research and discovery to produce.

For many reasons, certain research fields are growing more and more siloed. Many like to attribute this to the ‘burden of knowledge’—which suggests that it becomes harder to master multiple fields as the knowledge base of each grows. While this is to some extent true, it is not the type of problem that should be seen as insurmountable. Von Neumann’s work should serve as a stark reminder of this. Many great innovations in a field come from those who are not yet fully indoctrinated into the orthodoxy of the field. Having a complementary toolkit, a curious mind, and ignorance of the ‘best practices’ of a field is probably the most potent combination of traits that produce truly novel research in any given field.

Even if a researcher has all three of those things nowadays, they feel disincentivized to publish work outside of their own domain. Of course, not all researchers are excited at the thought of attempting to publish work in fields outside their main discipline, but many are. And, anecdotally, it seems that many of these curious individuals currently prefer to keep up with outside fields as hobbies and have conversations with researchers in those areas, but they don’t wish to undertake research with them. The issue of shared interest and conversation not turning into collaboration is one of the biggest issues facing the research community. There are likely hundreds, if not thousands, of researchers with the sharp, von Neumann-like tool of being able to expertly apply frameworks and tools of their own fields to solve problems in others that are stuck working on their own field’s problems exclusively. Moreover, that might be their only sharp research tool. And that would be a tragic inefficiency. Hundreds of individuals might be remarkably replaceable in their own field currently, but would prove irreplaceable if only given the proper incentive to seek out collaborations and problems in other fields.

Modern academic incentives encourage researchers to stay in their own lanes. And that needs to change. This kind of exploratory, bridge-laying work is hard and most ideas will come to nothing. But those ideas that do work out can often yield 100x-1000x returns to their fields. Researchers excited about pursuing these problems should have the red carpet rolled out for them! New science funders, existing grant-funders, and universities should be striving to create opportunities to encourage these kinds of explorations. There are countless, brand-new fields that could result from the almost random combination of interested experts with the problems of different subjects. It will often be completely non-obvious how one field’s toolkit can contribute to another’s. But if an expert researcher is motivated to explore a connection, they should be incentivized to try.

VCs adopted extremely founder-friendly policies for a similar reason. They acknowledge the leap of passion that founders are taking. Founders do not pursue the path of a startup because it is the easiest way to get rich. They pursue this high-risk strategy because they’re eager to do so; they are passionate. The biggest mistake a VC could make would be to disincentivize excited, prospective founders looking to bring brand new, exploratory approaches to an industry. But that is exactly what the academic ecosystem is currently doing with these researchers.

A Final Reflection on von Neumann-like creativity

My experience in grappling sports often informs how I conceptualize intellectual creativity. In my spare time, I do Brazilian jiu-jitsu. I mainly do Brazilian jiu-jitsu because, for a single high school season, I began wrestling and loved it. And, being an adult, it is easier to find a jiu-jitsu gym than a wrestling gym. They are both grappling sports, but the rules, body types, pace, and positions are completely different.

When it came to wrestling, my style as a beginner was considered as defensive and uncreative as it gets. I was a beginner just trying to grasp and execute basic concepts, and it showed. But when I later began jiu-jitsu, from my first day, my partners praised my creativity. I was finding new ways in and out of positions that many of my partners had never experienced before. What they were describing as creativity I knew by another name: wrestling basics. Even after almost two years in jiu-jitsu, where every day I learn more and more traditional jiu-jitsu techniques, my movements are described as increasingly ‘unorthodox.’

When you give a former wrestler and a lifetime jiu-jitsu practitioner the same lesson, they will take different things from it. When someone calls me creative or unorthodox, I feel like a fraud. “It’s just a wrestling background,” I think. In my own small way, this helps me understand what von Neumann must have felt when he said things like, “But didn’t anyone see that?” “It’s just mathematics and a bit of intuition,” he must have thought, over and over.

Some awed at Dirac because he could seemingly conjure up mathematical laws of nature out of the sky. And that is one form of creativity, one that is hard to purposely replicate. But von Neumann displayed an extreme case of another kind of creativity: the ability to find new uses for existing tools. His creativity seems more in line with combinatorial theories of innovation.

That which is creative need not be brand new, just a new combination of existing ideas. If these connections count as the kind of creativity a bird is meant to bring, then Von Neumann is possibly the king of all birds. He may not have been the bird with the fanciest coat like Dirac or Einstein, but his toolkit was one that kept on giving. This ability to expertly use existing tools to solve new problems left lasting impacts on almost every field he touched.

Once he made these connections, he would move on. The rest of cleaning up the field may have bored him. That is the kind of work a pure frog might relish and seek beauty in. But von Neumann was a different kind of animal.

A tale of von Neumann talking with a young John Nash reveals this may have been the kind of creativity he valued as well. To him, it may have often been more about building these bridges between fields than the problem itself.

In the meeting, Nash presented Von Neumann his Princeton graduate thesis that would eventually go on to win him the Nobel prize. His work had found a way to generalize von Neumann’s minimax theorem and pointed out that it didn’t just have to apply to zero-sum games. Von Neumann was unimpressed. He told Nash, “this is trivial.”

Von Neumann didn’t mean the thesis was bad. He believed it was a solid graduate thesis and very publishable. Von Neumann understood that Nash had found an elegant, generalized solution to games in which participants cannot talk to one another—a premise von Neumann didn’t love. But he just didn’t see anything in the work that was truly new. What von Neumann likely saw was, firstly, a fixed point proof, which von Neumann himself first brought to economics from the field of topology. Secondly, it was a fixed-point proof of a game whose formalization as mathematical logic was also first done by von Neumann. He likely saw Nash’s work as a reasonable extension on some of his own work. He was not rooting against Nash, this is probably just how he viewed creativity. No new tools were used to help solve this pre-existing problem.

This is obviously not the only definition of creativity; but, whatever you think of it, it seems clear that we need more of it. And, thankfully, how to generate more insights like this is not conceptually so complicated. We need to encourage more researchers to explore problems outside of their usual field of publishing. It should not be necessary that they have a concrete plan. They should be rewarded for their curiosity, for their curiosity has the potential to make major contributions to the system of knowledge. For these brave individuals, praise should be doled out for the expected value of their work and not the number of publications that make it on their CV.

If the existing academic ecosystem, with its old and rigid bureaucracy, will not allow this to happen, maybe one of the new grant-funders or some philanthropist will.

I hope you enjoyed today’s Engineering Innovation newsletter. Please subscribe for more pieces about Applied R&D and scientists. It helps a lot!

This post contains an Amazon Affiliate link.

Excellent article. Thank you for republishing it, i could have missed it if you didn't.

Modern scientific endeavors are a stultified and cultish mess of bureaucracy pushing against ever greater natural barriers of complexity. Even assuming someone like vN could survive 16 years of extraordinarily deficient modern American schooling to begin an approach to academia, it would be for naught.

Assuming his talent isn't passed over for belonging to a white male, he then joins a research group where he barely has access to his PI while investigating an extremely specific and relatively unimportant question for which funding was secured during the prior year. Use of equipment in deviation from this program is grounds for a grant audit. Regardless of results, the group must publish at least one paper per year to maintain funding. Data may be falsified.

Graduate coursework is even more strictly defined than undergraduate majors, and interdisciplinary study is strongly discouraged, as his credit-hours would be supported through the department by an R/TA. There is simply no time for him to waste studying such queer novelties as geophysics or molecular biology.

Midway through his PhD, he is informed in no uncertain terms that he must participate in a potentially hazardous medical trial or be suspended from the program. He declines, says his goodbyes to his group members (one of whom barely speaks English but seems like a nice guy), and departs for a happier life raising chickens, which he can afford because he was an early adopter of Bitcoin.