Today’s piece is a guest post by Karen Sarkisyan.1 Karen is the founder of Syntato, an applied crop genetics BBN. BBNs pursue ambitious North Star technical visions with a mix of contracts and grants. As Karen puts it, Syntato’s North Star technical vision is “computer chip design and manufacturing — but for plants.”

Karen is the perfect founder to present the first example of a modern BBN in this series. Syntato has both an extremely ambitious technical goal and a great customer — one that has enabled the org to be a break-even operation from day one. Beyond those attributes, Karen is an exceptionally effective writer.

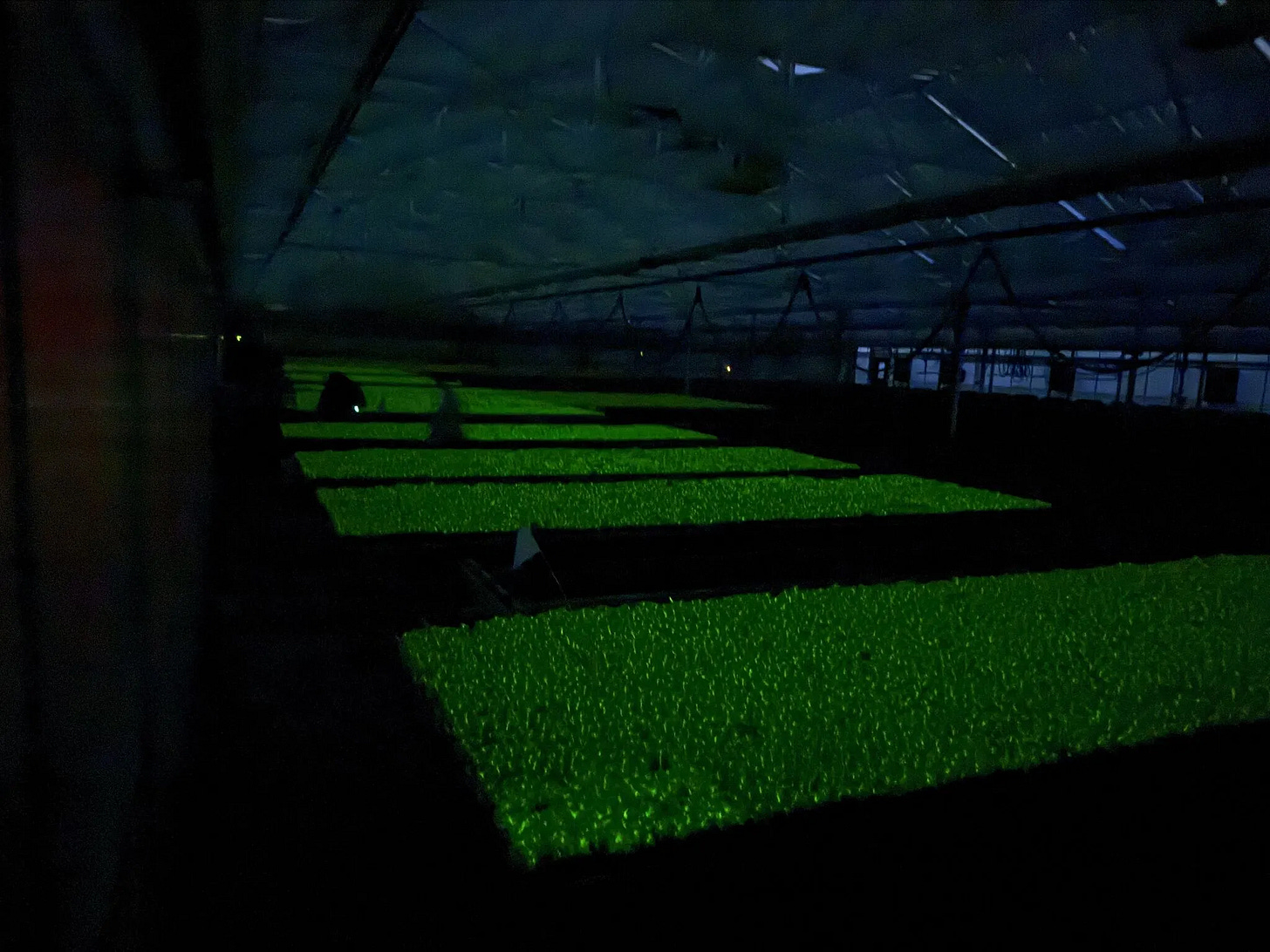

While Karen’s name may be new to readers, his work might be more familiar; Karen previously co-founded Light Bio. Light Bio inserts genes from fungi into petunias to make them glow (see below). Syntato’s work builds on methods developed at Light Bio and ideas from Karen’s research group at London’s MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences.

In today’s piece, Karen will paint a picture of where Syntato hopes to go. In reading it, I hope readers develop confidence that BBNs can swing big in the modern era while covering their own costs.

This piece is a part of a FreakTakes series on BBNs and the BBN Fund. To read more about the BBN Fund itself — and how great BBNs from ARPA history contributed to breakthroughs like the ARPAnet and early autonomous vehicles — see the opening piece in this series. TLDR: the BBN Fund will be a time-bound, thesis-driven fund at Renaissance Philanthropy, headed by Janelle Tam and me.

Our goal is to be for the BBN ecosystem what the best ARPA PMs are to speculative areas of R&D. As an alternative framing — to steal a new term from Nan Ransohoff’s excellent piece from a few weeks ago — we will be “General Managers” for the modern BBN experiment, directly responsible individuals dedicated to finding ways to lower the barriers to founding ambitious BBNs in the modern era. For us, success will mean paving the way for dozens of BBNs like Syntato to be founded per year. And we are actively seeking our first funders to make this happen. So if you are a funder interested in partnering with us, please reach out at eric.gilliam@renphil.org and janelle.tam@renphil.org!

With that, I’ll be out of your hair! Enjoy:)

From primitive engineering to the design of new plants.

By: Karen Sarkisyan

— How can we design a novel crop?

— Or program the behaviour of a house plant?

— Or turn a field into a super-organism that breaks the growth-defense trade-off through division of labour?

— Can we domesticate marine plants to produce food without deforestation?

Today, our ability to engineer plant traits is primitive. We are able to write one, two, and sometimes three lines of the lowest-level DNA code, and these programs are typically species-specific. None of the engineered plants on the market goes beyond the line:

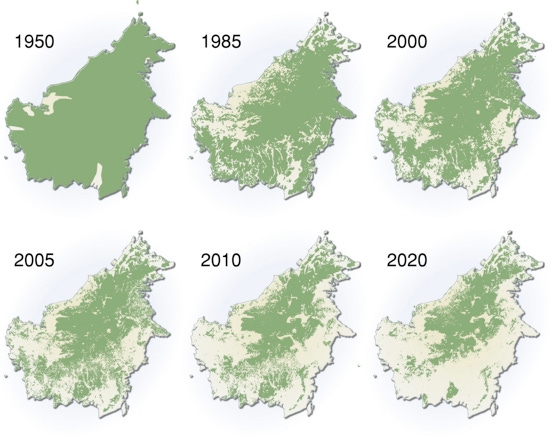

always express genes A-GIn the future, we may be able to design plant traits we need. But with the current rate of progress, this will not happen before our existing agriculture practices and need for energy and materials destroy most of the planet. (This image of Borneo deforestation, below, is one of the saddest things one can find on the internet — and there seems to be no realistic solution, except possibly an economic shift driven by biotechnology.)

— Is it possible to have a truly novel crop on the market in 10 years, by 2036?

— Probably not. Not with the current tools. And which team is even in a position to work on that?

Surprisingly, across the world, there are almost no competent teams working on ambitious plant engineering from first principles. Even the startups supposedly doing “cutting-edge” plant biotechnology almost always create yet another version of “overexpress genes A-G”. And most effort — shaped by regulations — goes into modifying existing plant genomes, one small edit at a time.

Several factors limit accessibility of deep plant re-engineering to biologists, most importantly:

difficulty of transforming and regenerating most plants, especially non-model cultivars,

lack of predictable building blocks to program plant traits,

immature “hardware” technology: molecular tools to build, host and update large DNA programs in plants.

Fortunately, plant transformation and regeneration (=1) has seen a lot of progress in recent years: a variety of novel tissue-culture-free (as well as tissue-culture-based) approaches have been developed [1, 2], with many studies already expanding way beyond model plants [3, 4, 5, 6]. We are certain that in the next 5-10 years, hundreds of academic groups will be trying out diverse approaches, largely removing this bottleneck without the extra help.

In contrast, predictable building blocks for programming plant traits (=2) remain scarce. Over the last decade, great work has been done standardising molecular infrastructure and creating collections of lowest-level DNA parts (promoters, genes, terminators) for different species of dicots [7, 8, 9, 10, 11] and monocots [12, 13]. However, very little work has been done at the higher level of genetic circuits and metabolic pathways.

Configuring pathways into openly accessible and easy-to-use building blocks lowers the technical “activation energy” barrier — with a non-linear, catalytic effect on their adoption. An illustration of this is the reporter RUBY which encodes biosynthesis of a red pigment: after being configured into the easy-to-use form of a single transcription unit in 2020, it is on the way to become one of the most popular reporters in plant biology [14, 15].

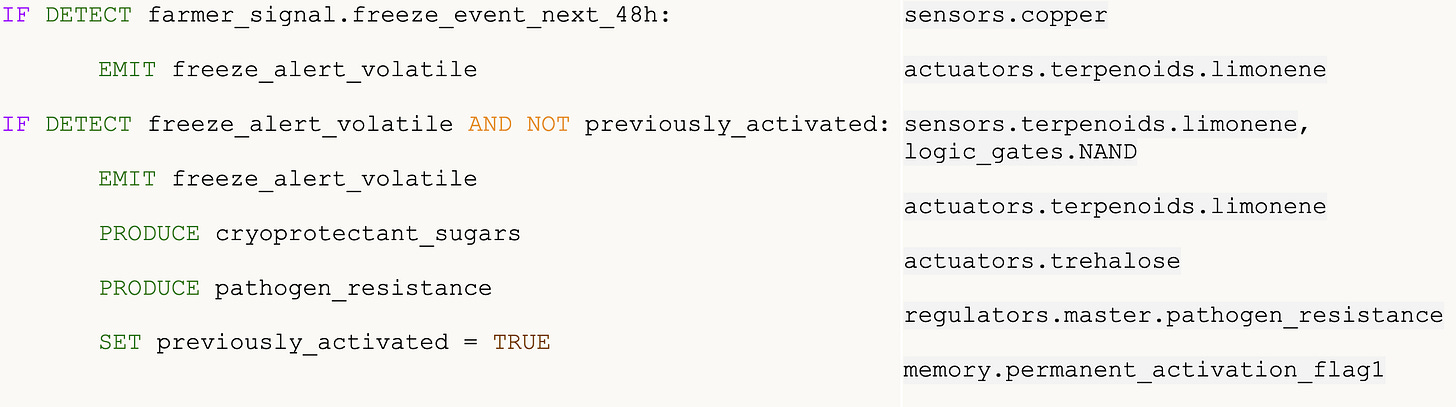

Let’s review a hypothetical program (on the left) and the building blocks needed to execute it (on the right). This program enables a farmer to deliver a critical weather forecast using a drone-sprayed chemical signal, helping plants survive environmental stress and maintain crop yield. To reduce costs for the farmer, the plants themselves propagate the information from the spray site throughout the field

Some of the building blocks required for such programmable traits have not been developed, despite the availability of components; others have only been shown to work as a proof of concept, but not as robust plug-and-play tools. An assessment of block compatibility and joint performance within higher-level programs has not even been attempted. There is no validated library of low-level genetic abstractions one can use to build a DNA program in plants.

Plant “hardware manipulation” technologies (=3) are at a similar place: we do not have solutions to routinely build and manipulate plant synthetic chromosomes, let alone do so at a cost compatible with iterative prototyping of large DNA programs. (This problem is the focus of Syntato’s ongoing ARIA-funded work — to create a technology to inexpensively build plant synthetic chromosomes.)

Due to GM regulations and the cost of obtaining regulatory approvals [16], there is little economic drive for enabling more complex plant programming. In the absence of such a drive, the current lack of tools and low-level genetic abstractions is unlikely to change soon: we are stuck without having the tools, despite the technology components already in place. A well-funded academic lab may attempt to work on this, but as the effort does not necessarily yield scientific novelty, but instead requires large-scale multi-year iterative refinement of genetic designs, it will be misaligned with the academic incentive structure. A startup cannot afford to do this general-purpose work, as it is too broad, expensive, and far from the market. A large seed company is unlikely to approve such spending as it’s not directly aligned with the goals of their crop development efforts. Without a focused effort for large synthesis of available technology to make good tools (“molecular hardware” & “DNA software libraries”), the activation barrier will stay high enough to prevent crop design from becoming accessible to a broad range of bioengineers.

By focusing on building tools, we aim to help move the field from the current primitive plant engineering towards the design of novel complex, adaptive traits — and eventually, just like we design computer chips today, we will design and manufacture genomes of new plants.

Contracts and grants

Syntato is the lead contractor on an ARIA-funded project to create plant synthetic chromosomes technology. It is a 3-year £4.1M+VAT contract, the budget of which is shared with collaborators and subcontractors. The contract with ARIA allowed us to buy equipment, build a small team, launch lab operations, and create a frontier screening platform for plant engineering work – all in under 9 months. This initial investment into the robotic infrastructure and technology created a basis to amplify the value of future grants and contracts: an opportunity to follow a BBN-style organisational path.

The platform we developed enables high-throughput experimentation in fully intact plant cells, with the highest reproducibility we’ve seen among plant biology transgenesis platforms. We offer two types of contracts:

Standard screening of customer’s genetic designs on our pipeline (cheaper, simple paperwork, no custom assay development, no IP ownership).

Tailored co-development of custom plant-based assays (more expensive, IP may be shared).

Syntato’s platform is universal and can be adapted to any plant species. It can be used for large-scale herbicide screenings, testing of AI-designed protein binders, directed evolution of proteins in plant cells, genetic circuit prototyping, and optimization of natural product biosynthesis. These services are particularly valuable for organisations without a strong plant engineering team or high-throughput plant testing capabilities. A use-case example would be a player in the horticulture industry interested in engineering a biosynthetic pathway to produce a pigment in an ornamental plant. Or a newly established startup that chooses to derisk their proof-of-concept on our platform instead of launching a fully functional lab. Or a seed company that outsources their protein engineering work instead of building that expertise in-house.

Essentially, if an organisation has a trait design project, we are excited to work with them. What makes the contract worthwhile for us is the customer's willingness to fund the upstream R&D necessary to make the desired outcome possible — allowing us to build tools and methods that get us closer to our technical vision. In that context, contracts that help move the whole field forward, such as those from philanthropic or government funders, are especially interesting.

What’s next

In Eric’s BBN Fund post, he wrote how the long-run organisational goals of BBNs will vary. One of the goals he mentioned was the possibility of using a BBNs base of contracts and grants to build up the equivalent of an academic department. This resonates with Syntato’s vision: we aim to use our contracts and grants to eventually grow into a larger research organisation, an engineering bureau that designs and creates plants. Doing this well would not just mean building up the technical equivalent of an academic department, but an entire research institute.

What would it take to reach that stage? We estimate a required volume of contracts and grants in the range of $3-7 million per year for about 10 years. We would love to work with a philanthropic funder willing to accelerate this work — please reach out to karen@syntato.uk if you have a lead. At the same time, we also feel that the customer-focused BBN path — the one which keeps us closely tied to industry’s real challenges — is the best path for Synato.

Thanks for reading:)

Karen’s LinkedIn, Twitter, and email — karen@syntato.uk .

Please let me know if you found this structure of today’s BBN write-up useful. The structure I personally tend to use is a bit more detailed, but in the same spirit. It goes something like: technical vision, contracts and grants, initial steps, distinct advantages, recruitment strategy, growth strategy, key winners, midterm assessment, and asks. We presented a simplified structure today, but I’m happy to adjust/expand based on reader feedback!

Karen is a part of RenPhil’s Frontier Research Contractors (FRC) pilot with ARIA in the UK, which helps BBN founders in the ARIA ecosystem better pursue their goals. You can read a bit more about this program in the opening post in this series. And if you’d like to learn more about the program, just reach out to me on Twitter or via email — eric.gilliam@renphil.org.