A year ago, I wrote a post saying I’d be taking a half-step back from this Substack in 2025. I adore writing FreakTakes, but I needed more time to throw myself into what I felt was the most important problem I could be working on: building more BBNs.

Since then, some version of the following paragraph has graced the top of an astonishing number of operational documents I’ve written.

A close reading of ARPA’s early history yields a key lesson: exceptional projects were usually the result of exceptional contractors. Now-famous ARPA success stories like the ARPAnet and early autonomous vehicles depended on a common shape of R&D organization — one structured, incentivized, and staffed differently than typical academic labs or VC-funded startups. I call this shape of organization a BBN-model org — named after ARPAnet contractor Bolt, Beranek & Newman (BBN). If R&D funders plan to chase more early ARPA-style outcomes, we should build more BBNs to do it.

Like FROs, BBNs pursue ambitious technical goals, ill-suited to the incentives of VC, that are too engineering-heavy or multidisciplinary for academia. Unlike FROs, BBNs primarily fund this work with a mix of contracts and applied grants, rather than a $10 to $100 million upfront fundraise.

This past year, I’ve embraced the role of a ‘field strategist’ for the BBN ecosystem.1 In this period — Stage 1 of the modern BBN experiment — I sought to verify that there was both demand for BBNs from ARPA-like funders and a supply of top researchers eager to found BBNs. Thanks to the UK’s Advanced Research + Invention Agency (ARIA), both have now been resoundingly verified. To provide just one data point in support: according to ARIA’s most recent fiscal year data, a small set of scrappy BBNs won more in ARIA funding during the year than every lab at the University of Cambridge combined. Stage 1 of the modern BBN experiment is now complete.

It is now time for Stage 2 of the experiment: building a “Convergent Research for BBNs.” The BBN Fund’s objective will be simple: seed a modern ecosystem of BBNs and work to maximize their overall technical ambition.2 If successful, we will forge a new pathway for today’s best applied, ambitious researchers to pursue ambitious R&D agendas — as Convergent Research has done with FROs. The team’s functions will fall into two basic buckets.

Capital Deployment. Using the capital we raise for the BBN Fund, we will deploy funds to drive the creation or growth of the most promising BBNs — using a mix of financial instruments including revenue-sharing agreements, revolving loans, and undirected R&D grants.

Field Building. Using the time of BBN Fund staff and affiliates, we will cultivate BBN founders, source new BBN customers and funders, and develop the scaffolding needed to grow the BBN ecosystem.

I will be founding the BBN Fund at Renaissance Philanthropy with Janelle Tam, formerly Convergent Research’s Head of Programs. She also built and ran Y Combinator’s Series A program, where she advised hundreds of early-stage startups on fundraising and growth. We are aiming to raise an initial philanthropic fund of $10 million to fuel this mission, and are looking for our first funders. Beyond the baseline costs of staff and field building work, for each additional $1 million, we believe we can help found or scale another ~5 BBNs. If we succeed, the J.C.R. Lickliders of our time will be able to build their life’s work within a BBN, rather than shoehorning their best ideas into academic-paper- or VC-shaped boxes.

In today’s post, I will paint a picture of our grand ambitions for the BBN ecosystem, and how the BBN Fund can get us there. The first section summarizes the BBN model for those who have not read prior FreakTakes pieces on the topic. The second section provides an overview of Stage 1 of the BBN experiment — ARIA’s embrace of BBNs and its partnership with Renaissance Philanthropy to provide grants and support to fledgling BBNs.3 I will end by presenting our vision for the BBN Fund.4

Today’s piece marks the start of a series. Each Friday for the next two months, I will turn the Substack over to someone in the growing BBN community, usually a founder, to write a piece on a new BBN-related topic. This will include:

Janelle Tam, my cofounder, on the potential to unlock large pools of capital for BBNs by demonstrating their potential as an investable asset class.

Karen Sarkisyan, a BBN founder in the UK, on his new applied crop genetics BBN.

Henry Lee, CEO of Cultivarium — the non-model organism FRO — on the prospect of transitioning his FRO into a BBN.

Tom Milton, CEO of Amodo Design — a BBN with the desire to fold toolmakers back into the early stage science process — on the rate at which BBNs can grow, and what drove his org’s ability to increase its largest contract by an order of magnitude four quarters in a row.5

And more! Stay tuned.

If you are (or know people who are) interested in becoming a BBN funder, founder, or customer, reach out to us at eric.gilliam@renphil.org and janelle.tam@renphil.org.

The BBN Model

Simply put, BBNs pursue ambitious North Star technical visions with a mix of contracts and grants. The shape of technical ambition will vary. It can range from an FRO-like technical goal, such as developing methods to cheaply map mammalian brains, to building a center of excellence in an area of R&D in which academia struggles, such as bespoke biotech instrumentation or chip building.6 Some BBNs may even pursue the speculative work necessary to help establish new subfields of research, e.g. computational law. What unites BBN founders will not be the shape of their technical visions, but their capacity to fund them by solving real problems for paying customers en route to these visions.

At the original BBN, J.C.R. Licklider leveraged the model masterfully to pursue his technical vision: building a future of interactive computing. It was at Bolt, Beranek & Newman that Licklider took his first step away from his MIT professorship and towards building this future. Similarly, CMU’s 1980s autonomous vehicle teams leveraged the BBN model to tackle their own FRO-like problem, succeeding in building autonomous vehicles where DARPA’s prime contractors could not and academic computer science would not.

In pursuit of Licklider’s vision, a series of technical problems related to both UX and real-time computing needed to be knocked down. The BBN computing group did just that in the 1960s by utilizing a set of cleverly assembled contracts and grants from groups like the NIH, NASA, ARPA, consulting projects with industry, and other contract partners. The group did this while building a research culture at the firm that earned the admiration of MIT professors and affiliates, many of whom described the original BBN using phrases like “the third great university of Cambridge,” “the Cognac of the research business,” and the true “middle ground between academia and the commercial world.” Licklider and others left positions like MIT professorships to join the firm. They felt it was a far more resonant research environment for their applied, ambitious research than MIT.

BBN’s computing team was able to strike this balance between ambition and contracting because they only worked with customers whose needs were exceptionally aligned with their technical vision. One example of an aligned contract was the firm’s contract to build an NIH-funded hospital time-sharing system. This contract, which was key in funding BBN’s real-time computing progress, was ostensibly a contract to build an administrative computing system for Massachusetts General Hospital. While BBN did not necessarily care that much about building computers for doctors, the team embraced the work because it funded years of real-time computing R&D en route to its technical ambition — R&D that was then too speculative for industry and ill-suited to MIT.

Like FROs, BBNs will tend to have ambitious goals that are too engineering-heavy, multidisciplinary, or applied for academia. And they will tend to focus on markets ill-suited to VC — either (a) because these are not billion-dollar markets, or (b) because the financial impact of the work could be massive, but will not be realized within the ~10-year life of a VC fund. The latter scenario was likely the case for both the ARPAnet and autonomous vehicles.

Like FRO founders, common BBN founder archetypes will include applied-minded postdocs, research-minded engineers, defected professors, and former deep tech founders who crave the longer R&D timelines and research flexibility that the BBN model allows. BBNs won’t build and hire as fast as FROs on day one, as they will usually have much less capital. In choosing the BBN pathway, founders trade the practicality of an upfront ~$10 million FRO fundraise for a different kind of practicality: finding a set of customers and applied funders whose needs are aligned with their technical vision. Like startups, if they are able to tap into a sustainable base of funding, they can steadily expand in pursuit of their technical vision, learning as they grow. Many inspired technical visions will not have a corresponding customer base, of course. But wherever you have an ambitious researcher with vision and an aligned set of customers/funders, you might have a BBN.

Early ARPA’s best BBNs shared three distinct traits, rarely found together in R&D labs. Each:

Was novelty-seeking or technically ambitious, with a strong preference for projects that pushed the technological frontier forward substantially.

Built useful technology for paying customers. This entailed professional contract management and a willingness to focus on difficult systems engineering tasks. Many BBNs were relatively indifferent to market size, so long as they could find adequate contracts and grants to pursue their North Star technical vision

Used more flexible team structures than academia. When compared to academia, they more effectively hired, organized, and incentivized researchers, engineers, and other experts to collaborate on applied projects in a common-sense fashion.

With a set of aligned contracts and grants, BBN founders can often begin working towards their technical goals with only a few hundred thousand dollars — some BBNs can even be bootstrapped. This path comes with a level of ongoing financial risk not present in FROs — at least not FROs that have successfully fundraised. But fundraising for FROs is a bottleneck that few presently pass. The BBN model empowers talented, practical individuals to get in the game using a scrappier model. We believe that by lowering the barrier to entry, in five years, dozens of BBN teams could be founded each year. That means dozens of founders or technical leads setting out on the path towards their ambitious technical vision in a research environment that is both resonant with their goals and cost-offsetting.

Stated plainly: the goal of The BBN Fund is to enable the work of the next J.C.R. Licklider. And based on the exceptional results of BBNs with ARIA so far, we believe this is a realistic goal.

(For a thorough piece synthesizing the BBN model, see A Scrappy Complement to FROs: Building More BBNs.)

Stage 1: BBNs’ Success with ARIA

Stage 1 of the BBN experiment sought to verify the demand for BBNs from modern customers and the supply of talented potential founders. The UK’s Advanced Research + Invention Agency (ARIA), led by fellow metascience nerd Ilan Gur, was singularly important in running this stage of the BBN experiment. But Ilan and ARIA were not specifically trying to run this experiment. They were just trying to find some way, as Ilan might frame the goal, “to find the right people, in the right institutional environments, with the right incentives” to drive ARIA’s technical agenda forward.7

ARIA’s flexible procurement rules made this possible. Its Programme Directors (PDs) are empowered to make large bets — even multi-million dollar bets — on orgs that are young or brand-new, run by individuals ARIA feels are the best on Earth to get a job done. How flexible were these policies, exactly? As Ilan proudly shared when I interviewed him for Asimov Press, when individuals like postdocs fill out ARIA grants, ARIA has taken the unusual step of enabling them to check a box that allows them to accept the grant as new, independent research orgs. They can staff themselves with multidisciplinary researchers and engineers, negotiate contracts without involving university admins, tackle projects academia does not incentivize, pay people market rates, etc. In essence, they can spin up BBNs.

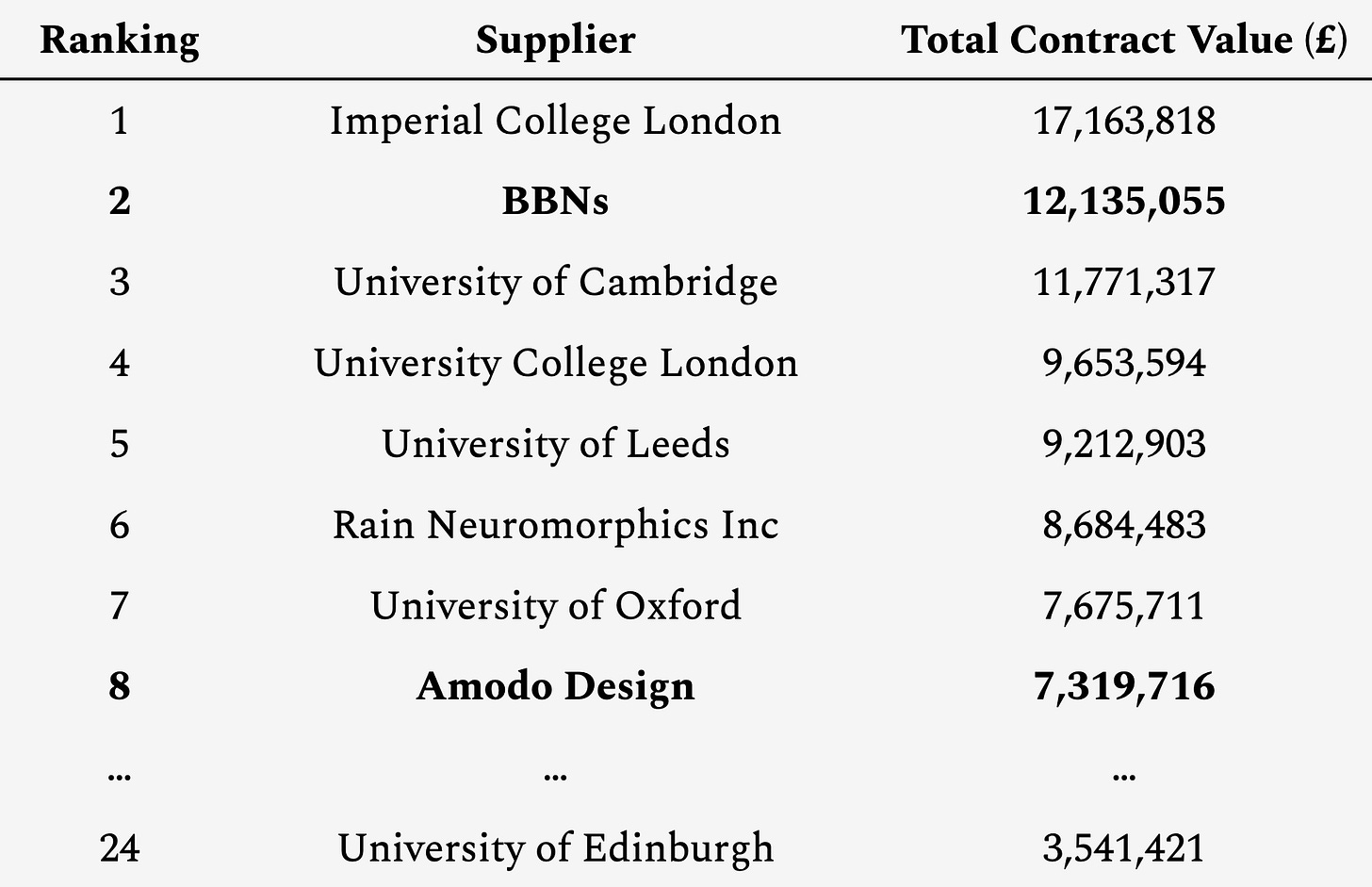

Less than two years into funding R&D projects, ARIA-funded BBNs are performing exceptionally. To contextualize how exceptionally, I’ve put together the following table using the agency’s recent fiscal year data. The table seeks to answer the question, “If the few BBNs in the ARIA ecosystem were a university, how would the ARIA funding they win compare to other UK universities?” The answer: BBNs won more ARIA contracts than every university in the UK except one, outperforming even the University of Cambridge.

Amodo Design — whose CEO will write a guest post in this series — was, on its own, neck-and-neck with the University of Oxford. And excluding Amodo, the rest of the combined set of BBNs still won more contracts than top universities like the University of Edinburgh. And more BBNs are coming. Syntato, an ARIA-funded BBN with a technical ambition to build an ARM chip design for plants — whose proposal you will read in Week 3 of this series — was not even included in this data, for example. While any specific ranking in that table should be taken with a grain of salt — contract award data is lumpier than reality — the fact that BBNs immediately find themselves in the mix with the UK’s historical research giants is a major early data point indicating that BBNs might have as big a role to play in this century as they did in the last one.

The question is no longer, “Is there any demand for BBNs from modern funders?” Stage 1 of the modern BBN Experiment has been completed. Ilan Gur and the team at ARIA — in their search to have their problems solved by aligned R&D groups — have seen to that.

Momentum is building. ARIA has even set aside a yearly pot of £400k for a program with Renaissance Philanthropy to help found and scale BBNs aligned with ARIA’s goals. Several individuals from ARPA-like agencies in other governments have also begun reaching out to discuss similar programs to serve their own needs. Most importantly, the BBN founders themselves — a boundless source of ideas — are constantly finding ways to reach new types of customers — from hedge funds to academic labs — that can preserve their technical ambition and pay the bills. The time is ripe to undertake Stage 2 of the BBN experiment: the BBN Fund.

Stage 2: The BBN Fund

The BBN Fund will act as the vehicle to orchestrate this experiment in “applied metascience.”8 Our focus will be to help build more and more ambitious BBNs. In operating this experimental, nonprofit fund, we plan to deploy funds in ways that answer questions relevant to BBN-curious funders — both nonprofit and for-profit. How technically ambitious can BBNs become with a modest amount of undirected R&D grants? Under what circumstances can investments in BBNs not only push the frontier of scientific progress, but also beat index fund returns on a risk-adjusted basis?

We plan to answer questions like this with economy and speed. The capital we raise will be used to seed BBNs, and we will learn, by doing, how to found and manage BBNs in the modern era.9 The two levers we will rely on to do this work will be the time of BBN Fund staff and capital from the BBN Fund itself. The rest of this section will summarize our approach to using both.

Capital Deployment

An exciting characteristic of BBN founders is their ability to balance practicality and grand ambition. From day one, BBN founders design their org with practical realities, such as customer sales cycles, in mind. But even with practical planning from the founder and a set of aligned customers, several financial problems hamper the creation and growth of BBNs. The BBN Fund will leverage three financial instruments to overcome these problems. Each instrument, in its own way, will enable us to leverage the practicality of the BBN model to stretch R&D funding dollars abnormally far.10

But before discussing these instruments, let’s talk about the problems. The first is temporary cash flow problems. Even if a new BBN wins some contract, it may have cash flow problems for several months (at least), as contract expenses are often front-loaded. The second problem is startup capital needs. Many BBNs will require a modest injection of funds — the equivalent of a seed round — to do the technical and operational work necessary to become self-sustaining organizations.11 The third problem is ongoing research funding needs. For many BBNs, the flexibility provided by winning something like ~20% of their budget as undirected, NSF-style R&D funds — for investigations, core technology development, etc. — can make the org ~twice as technically ambitious.

The three financial instruments the BBN Fund will experimentally deploy to help founders overcome these problems are low-or-no-interest loans, revenue-sharing investments, and undirected R&D grants. While loans and revenue-sharing agreements are peculiar instruments in the world of philanthropy, we believe they might enable us to stretch a fixed pot of capital exceptionally far. Below, I describe the promise of each instrument in more detail.

A Revolving Loan Fund. Low-or-no-interest loans with no collateral requirements will enable far more founders to spin up BBNs. Several existing BBNs had to bootstrap, including Amodo Design. That is admirable, but presents a barrier to entry for many prospective BBN founders, limiting the scalability of the model. Judiciously applied, low-interest loans can provide instant access to capital to cover the salaries, equipment, leases, and other expenses BBN founders have to pay upfront to win and execute contracts. These instruments will have the same limited downside risk for founders as VC funding. Given out as loans instead of grants, the revolving loan fund offers the opportunity to spend dollars multiple times. Any repayment above 0% will drive a higher ROI than the status quo. That being said, with prudent decision-making, most of the capital loaned out can be paid back into the fund — many BBNs asking for loans will have a high payback rate, as they will already have warm contract leads. In the case where ~80% of funds loaned out are revolved back into the fund within 18 months, we can create ~five times as many BBNs using a fixed pot of capital, compared to deploying the funds as undirected R&D grants.12

Revenue-Sharing Agreements. The BBN Fund will experiment with BBNs as an investable asset class. We will identify scenarios and strategies in which investing in BBNs can be attractive to certain private investors and philanthropic funders. In my discussions with BBN founders, revenue-sharing agreements have been the most common category of instrument proposed to facilitate these investments. And I have yet to meet a BBN founder who, for a fair price, is categorically against partnering with a for-profit investor, sharing the upside with them. To lower the barrier to engaging in these revenue-sharing agreements, the BBN Fund will design a fit-for-purpose, YC-SAFE-style instrument to facilitate these agreements. Ideally, this instrument would allow the following deal terms to be customized to match any given situation:

Percent of Revenue Shared

Revenue Base (i.e., is revenue calculated from overall revenue, a certain line of business, etc.)

Sunset Clauses (e.g., no payments after 8 years, once 5x the original investment is paid back, no sunset, etc.)

Grace Period (e.g., no repayment expected for first 18 months)

Even in cases where the returns on these agreements do not outperform index funds on a risk-adjusted basis, they can still prove to be an exceptionally cost-effective tool for philanthropists and impact investors.

Undirected R&D Grants. Many BBNs require modest levels of undirected R&D funds to effectively pursue their technical visions. These funds do not need to be the majority of their budget, but can often be in the range of ~20%. This minority of funds, and the flexibility they provide, can be vital in differentiating the work of certain BBNs from a typical, unambitious contract research organization. While it will only be a minority of the fund, when it is cost-effective, the BBN Fund should deploy undirected R&D grants to BBNs. One exciting characteristic of even this ‘free money’ is its relative cost-effectiveness when compared to undirected R&D grants to labs that don’t take on contracts. E.g. If a BBN can fund ~80% a course of R&D via contracts that other groups would have asked philanthropists or the NSF to wholly fund via undirected grants, the extra ~20% in undirected grants needed to top off their budget should come as an obvious bargain.

Through our efforts, we hope to make BBNs a legible vehicle for investment for both philanthropic funders and for-profit investors. While we are a nonprofit fund that will reinvest any revenue-sharing profits into BBNs, we hope as many types of BBNs as possible prove to be profitable. That is because one of our goals is to stimulate a BBN investment market into existence. Profitable investments from our portfolio will serve as a proof-of-concept to investors that certain types of BBNs are a profitable asset class. And in those areas in which funding BBNs carries a negative profit margin, and seek philanthropic backing, we will obsess over cost-effectiveness all the same. We aspire to become one of the most cost-effective forms of scientific philanthropy on Earth — the group that, while ruthlessly selecting for ambition, still found a way to spend each dollar multiple times.

BBN Central Office

If the goal of the BBN Fund’s capital deployment is to create and amplify the ambition of BBNs via financial investments, BBN “Central Office” will do so through the direct effort of a small group. This group — Janelle and I for now — will be the hub of BBN field building, dedicated to addressing the non-financial bottlenecks that currently limit the growth of the BBN ecosystem.

In many ways, Central Office will be looking to scale and expand on my own field strategy efforts over the past year. At Renaissance Philanthropy, wearing my BBN field strategist hat, I spent significant time on the following tasks:

Sourcing new BBN funders and customers, helping them understand which of their problems are BBN-shaped, and how I might source a BBN founder to solve those problems.

Cultivating new BBN founders, finding exciting founders with aligned ambitions, and helping them understand that a BBN might be an exciting vehicle in which to pursue their life’s work.

Field Building. In addition to my ARIA work, I’ve been able to use FreakTakes as a vehicle to excite readers — some of whom inhabit important positions in the R&D ecosystem — about the possibilities of the BBN model. This has driven an increasingly impressive flow of founders and funders my way, as well as helped bring existing BBNs together under one banner, with one common vocabulary.

Through my and Renaissance Philanthropy’s field strategy efforts, we’ve already had a hand in unlocking over $10 million in funds for BBNs.13 Our goal is for every dollar spent on BBN Central Office to unlock 10X as many funds from other customers and R&D funders through similar efforts. So far, we’re on track.

Scaling the above tasks will include accomplishing key goals like ensuring that, for every BBN founder, every aligned ARPA-style PM or philanthropic grant officer on Earth is one warm introduction away, and ideally is briefed on what BBNs can do for them before calls for funding go out.14 We’re excited to find ways to tackle these problems. In addition, we will concern ourselves with a variety of other bottlenecks that repeatedly come up when talking to founders. Each could unlock an order-of-magnitude more capital for BBNs than they cost to address. A sample of these tasks includes:

Sourcing aligned, practical mentors. While BBNs are meant to be far more ambitious than typical contract research organizations (CROs), some have CRO-like revenue streams. That’s great, if it can fund their technical vision! But there’s a problem: many PhDs from places like MIT have never met anyone who runs a CRO. As top researchers now look to build BBNs in this area, we need to find mentors to show them the ropes.

Sourcing aligned contractors. Similarly, Central Office will establish relationships with individuals needed to make commercial sales. Some BBNs have floated the idea of selling data from instruments they build to commodity traders, to offset costs. If this proves to be a common need, we will find data brokers who can explore and facilitate these contracts.

Unlocking NSF-style grant funding. NSF and NIH grants can prove to be reliable sources of R&D funding for BBNs. But accessing NSF-style funds is not yet as straightforward as it should be. Certain BBNs claim they cannot win NSF grants at the rate they did at universities. One advisor believes this might be a problem of know-how, and is eager to work with a few BBNs to try to increase their win rate in applying for these grants.15

One way or another, it is our job to solve these problems for BBNs.

Small Teams, Large Shadows

The biggest upside of funding BBNs is not even their cost-effectiveness, but their potential to unlock categorically different research than existing institutions can provide. The original BBN delivered the first four nodes of the ARPAnet on time and under budget, for approximately $8 million today. This was a contract that companies like IBM ‘no-bid’ because they thought it was impossible. Early CMU’s autonomous vehicle teams accomplished technical breakthroughs that DARPA’s prior prime contractor failed at with 10x their budget.

The 20th Century’s great BBNs demonstrated that in R&D, with a differentiated model, small teams can cast a large shadow. Charting their own research path with a mix of contracts and grants, BBNs have a measure of freedom to direct their research agendas towards differentiated outcomes — with no worry for what’s unpopular in academia or ill-suited to venture incentives.

For years, I’ve obsessively studied historically-great R&D operations of many shapes and sizes. Based on my experiences with BBN founders and customers this year, I believe the BBN model can be a vehicle for the right founders, in the right situations, to fund a range of these orgs into existence. This includes:

Bootstrapping new academic departments. The BBN model can enable founders to bootstrap (what are essentially) new academic departments into existence, outside the university.16 17 18

Funding industrial R&D labs into existence. BBNs are, in many ways, self-sustaining frontier labs. Under the right circumstances, the BBN model may prove to be a way to make a dent in the problem of funding more groups like early DeepMind into existence — without the pressure to appease investors and exit to a high bidder.19

An alternative approach to deep tech VC. With a bit of taste, we might demonstrate that investors can reliably pick modestly profitable firms when making revenue-sharing investments into BBNs. If savvy investors can reliably identify 3x outcomes, with 20x outcomes from time-to-time, a world of possibilities opens up in which BBNs can not just beat index fund returns from a financial perspective, but fund wildly ambitious R&D projects along the way.20 (Janelle will dedicate next week’s post to painting a picture of this possibility.)

The BBN Fund is being created to run this experiment and find out what’s possible. If the model proves capable of creating any of these types of orgs, in bulk, that would be a big deal. As of now, we believe the model might be capable of doing all of the above, at least some of the time.

While the Midwesterner in me blushes to speak of grand ambitions, in philanthropy, I believe ambition is a moral duty. We will not aim small. Our ambitions, over the long run, should be measured in metrics like Turing Awards per dollar, number of BBNs doing the most interesting work in their area, or the number of entirely new industries created. If the NSF and NIH annually spend $50 billion to return ~4 Nobel prizes, we will strive to be 100x as efficient.21

These are grand goals, but they are not crazy goals. The $8 million spent on the ARPAnet seems to be less than 1% of that year’s NSF budget. CMU’s initial NavLab vehicle breakthroughs were done for ~1/1000th of that year’s NSF budget. These were exceptionally cost-effective uses of R&D dollars — maybe some of the best in the history of US public R&D — and they were done by BBNs.22 Let’s build more of them.

If you are an interested funder, customer, or aspiring BBN founder, please reach out — eric.gilliam@renphil.org and janelle.tam@renphil.org, or dm me on Twitter.

As always, thank you to my faithful editors, Toren Fronsdal and Tristan Wagner. They have edited this and every other FreakTakes piece. Every piece would be longer and less intelligent without them.

And thanks to Adam Marblestone,23 Tom Kalil, Janelle Tam, and Tom Milton for each —in different ways — changing how I conceptualize what might be possible with the BBN model.

If you’d like to read more about R&D groups from history that worked in BBN-like ways, or with lessons to teach modern BBNs, check out the following FreakTakes pieces. Each paints a picture of how orgs fueled by contracts can raise the ambition of the R&D ecosystem.

“The Third University of Cambridge”: BBN and the Development of the ARPAnet

An Interview with Chuck Thorpe on CMU: Operating an autonomous vehicle research powerhouse

Edwin Cohn and the Harvard Blood Factory, for Asimov Press

A Progress Studies History of Early MIT— Part 2: An Industrial Research Powerhouse

How did places like Bell Labs know how to ask the right questions?25

Through my role at Renaissance Philanthropy, finding ways to grow the BBN ecosystem with philanthropies, ARPAs, etc.

This will be in the form of what Renaissance Philanthropy calls thesis-driven philanthropic funds. You can read more about this structure here.

This work — a part of RenPhil's (broad) ARIA Activation Partnership and its (BBN-specific) Frontier Research Contractor Launchpad program is specifically focused on assisting BBNs aligned with ARIA's technical agenda. This agenda is represented by areas of technical opportunity in which ARIA is particularly excited to run programs, which it calls "Opportunity Spaces.

The quote that accompanies the image was written by BBN cofounder Leo Beranek, describing Lick’s obsessive use of BBN’s first computer, a $30,000 Royal-McBee. I was happy to find an image is of Lick demonstrating this trademark vigor along with the smiling nature, which Beranek also noted. In the image, Lick is using the PDP-1 he had the firm buy two years after they had bought their first machine, the Royal-Mcbee.

And, as Tom noted in our WhatsApp correspondence, “doubling year on year since then.” For reference, Amodo was a bootstrapped org that built some of its first contracts out of a founder’s living room.

To provide a historical example demonstrating that, with an aligned set of customers, BBNs can pursue FRO-like technical goals, take the early CMU autonomous vehicle teams. In another world, these teams could have operated with an FRO structure. But in practice, in the 1980s, they operated using a model more similar to BBN’s contract research model. And this group made so much progress that they were able to drive a vehicle cross country 98.5% autonomously in 1995, using a neural net-powered steering system and other advances funded by their DARPA contracts.

Wherever possible, Renaissance Philanthropy and I, in our field strategy efforts, attempted to connect potential founders who might serve ARIA's needs to ARIA, worked with fledgling founders on questions of BBN strategy, and worked to understand Programme Director’s problems that might be solved by BBNs. More details on this field strategy work come in a following section.

A Renaissance Philanthropy fund, to be clear.

With success, in the next five years, we hope to create a world where dozens of BBN teams are created each year. And we hope many of these BBNs do not rely on undirected philanthropic grants to survive, but, rather, a more sustainable mix of contracts and grants.

If curious, a wonderful complement to this section is Alex Obadia’s — former tech entrepreneur and current ARIA PD — piece: Wanted: New Instruments to Fund BBNs

As with the loans, this can include capital to cover the salaries, equipment, leases, and other expenses BBN founders have to pay upfront to win and execute contracts. In general, both of these instruments will be used to fund a variety of the work needed to survive a key early period which must be overcome before an org can be self-sustaining. E.g. to cover a brief period in which academic users are eagerly using your tools, but they need to write you into their next grant to pay you adequately.

Another question we’d seek to answer using the BBN Fund: If a philanthropy hands out $1 million in low-interest loans to help found BBNs with warm customer leads in X area, how much money is paid back on average?

The above field strategy tasks represent some of the work Renaissance Philanthropy and I have undertaken with ARIA in this work.

For reference, when I meet with ARIA programme directors (PDs), the value add/pitch goes something like, “The goal of my work is to make it so that, as you design your program, you don’t have to take the contractor ecosystem as fixed.” This makes a difference. People are often happy to tell you about the specific problems they are working through. And if there’s alignment, I try to help. These are not secrets, but it’s also not as if every philanthropic program officer has their own Substack to explain their current thinking on some matter. You have to go out of your way to understand their problems, just as entrepreneurs do with customers. As a side note, it’s been a real pleasure to have these discussions with the ARIA PDs — some of the more fun interactions of my professional career.

We hope to build towards a future where BBNs can attain the majority of their basic research budget from NSF-style entities. Given recent NSF initiatives ranging from TechLabs to the TIP Directorate, we are optimistic.

The Topos Institute, an applied category theory BBN covered in an earlier piece on this Substack, has built up the kind of culture in which a Turing Award winner regularly comes for visits, often just for fun, as researchers often do to academic departments

Pre-World War II MIT is an obvious example that great research departments can be largely industry-funded. The FreakTakes Progress Studies History of MIT Series, — particularly Part 2: An Industrial Research Powerhouse — covers this at some length. MIT’s Technology Plan — a program in which MIT made a coordinated push to provide contract R&D and other services to industry — is the clearest example of this. As William Walker, one of the founders of modern chemical engineering practice, framed the work, “There could be no more legitimate way for a great scientific school to seek support than by being paid for the service it can render in supplying special knowledge where it is needed.” At one point, during this period, MIT’s applied chemistry department became 6/7ths industry-funded.

BBNs can also be a great vehicle to spin up what I call “Compton Model Research Departments.” This model of academic research department — named after WWII-era MIT President Karl Compton — in which one or a few great individuals control an academic department and its resources, steering it towards a specialized set of goals. This is in contrast to the status quo in which each professor gets their own small budget, their own small teams, and departments attempt to hire somewhat broadly to try and cover the breadth of what is going on in a field at a given time. Compton — a Princeton physicist and longtime GE Research contractor — pushed for the model because, as he saw it, the effective management and coordination of these departments towards shared goals enabled a situation in which “the output has greatly exceeded the individual capacities of the research workers.”

Many in the progress studies community wonder how we can build “modern-day versions of Bell Labs.” While certain aspects of Bell Labs model are not straightforward or not worth the effort to replicate, the general point is a phenomenal one. And, in many cases, relying on the VC ecosystem to fund these orgs into existence doesn’t make a lot of sense, incentive-wise. In many instances, what’s optimal is a field strategist with great technical vision to run the group and control its governance, as J.C.R. Licklider did at BBN. It’s possible that these groups might wish to raise VC money after some breakthrough — or facilitate a VC-funded spinout — but working through many iterations of R&D before entering the VC ecosystem can be preferable, even in VC markets.

This is an approach to deep tech venture creation similar to that of early MIT — whose golden era of deep tech VC coincided with its golden era of contract R&D. In addition to the FreakTakes Progress Studies History of MIT, I’ve covered early MIT’s approach to deep to deep tech venture creation, specifically, in An Alternative Approach to Deep Tech VC.

Their goals are more complicated than this, as ours will be. I was simply taking this moment to put into the reader’s mind the overall budgets of the NSF and NIH and the single biggest marker of success in academic research. As you’d expect, for somebody who routinely writes 10,000-word Substack posts on niche R&D history topics, I have a three-page internal document summarizing just a few of these goals. So do not be concerned, we will be measuring ourselves using much more than Nobels per dollar — which are given out on a delay, only exist in certain areas, etc. etc.

In the introduction to a later piece, I will explore some of the (accidents of) history behind how the BBN model waned in popularity in the later 20th Century. Firstly, as technical universities (e.g. midcentury MIT) abandoned R&D contracting to focus on winning NIH and NSF grants, it eliminated a key pipeline for prospective BBN founders — PhDs who, in working on these contracts, developed the know-how and relationships needed to build contract businesses. Secondly, the best BBN customers of the prior generation (e.g. DARPA, NIH, NASA) often grew more bureaucratic, particularly in their procurement processes, making them more difficult for young, hungry founders to work with. Thirdly, this coincided with the rise of venture capital, in which VC-funded startups replaced BBNs as the main path for talented graduate students to start firms.

Things are now different. New customers have sprung up that are as flexible as early ARPA — like ARIA, AI labs, hedge funds, and billion-dollar philanthropies run by exited tech founders. For one reason or another, disenchantment by young researchers with what they see as the academic rat race, disappointing academic problem selection, etc. have created a generation of applied-minded graduate students often seeking alternative paths to do research. Additionally, after some trial-and-error, it’s become clear that venture is often a poor way to fund the risky, long-term research core to ambitious science. It’s a tool for lucrative, special cases. Through these shifts — along with the late 20th Century shift away from ambitious, corporate industrial R&D labs — we have gotten to observe those areas in which the American R&D ecosystem has become hollowed out in response to the shifts described. Our goal with the BBN Fund is to learn from this history and capitalize on the current moment. We intend to build a dynamic ecosystem of BBNs fueled by ambitious (often young) researchers looking to adopt this old new model of research org; they will use it to fuel their own ambitions.

It was, in fact, a conversation with Adam that allowed me to steel my nerve and feel comfortable throwing myself into this work. I felt nobody would know better than him what I should do. His encouragement went a long way.

It’s possible that the ill-fated Thinking Machines Corporation may have had a less tumultuous existence as a BBN, compared to the complications it experienced as a venture-funded firm, in which many of its first-rate research staff — and possibly its CEO — cared more for technical ambition than building for the most lucrative business use cases.

This piece contains lessons on how BBNs might find aligned customers, choose research questions, etc.

You AND Janelle? Rocking team. Excellent news.

beautiful