When do ideas get easier to find?

And why progress studies may be much older than you think

The public has a distorted view of science because children are taught in school that science is a collection of firmly established truths. In fact, science is not a collection of truths. It is a continuing exploration of mysteries. - Freeman Dyson

Since the last article on WW2-era German science was so well-received, I’ve decided to keep the theme of great pieces of scholarship about scientific history going. This week’s post is largely drawn from the essays of Gerard Holton. Holton’s work is, similar to the scholarship covered in the previous post, criminally under-talked about in the progress studies community. The Holton essays I talk about in this post, largely written between the early 1950s and 1970s, have lasting relevance today.1

Holton would have been best described as a scientific historian; however, as you’ll see in the modeling section of this post, his contributions go beyond that of an ordinary historian. The application of his physicist’s mind and toolkit to the problem of scientific innovation was incredible. Nowadays, we might consider him a social scientist who studied science itself, an early progress studies scholar. And a great one.

In this post I’ll go over:

Holton’s thoughts on why it was VITAL that we establish a science of progress, which he called S₁

Holton’s assumptions under which ideas get harder to find vs. easier to find over time

And how we may have built a world where ideas are now becoming harder to find; also, why new science orgs should be investing in ‘branch-finding’ to try to help regain our once-explosive idea-finding productivity

S₁: The Science of Progress

Princeton physicist, H.D. Smyth, said at the time of Holton’s writing, “We have a paradox in the method of science. The research man may often think and work like an artist, but he has to talk like a bookkeeper, in terms of facts, figures, and logical sequence of thought.” And while this staid, accountant-like language helps in communicating public findings and settling scientific disputes, it is not helpful in the study of progress itself.

Holton noted:

Most of the publications are fairly straightforward reconstructions, implying a story of step-by-step progress along fairly logical chains, with simple interplays between experiment, theory, and inherited concepts. Significantly, however, this is not true precisely of some of the most profound and most seminal work. There we are more likely to see plainly the illogical, nonlinear, and therefore “irrational” elements that are juxtaposed to the logical nature of the concepts themselves. Cases abound that give evidence of the role of “unscientific” preconceptions, passionate motivations, varieties of temperament, intuitive leaps, serendipity or sheer bad luck, not to speak of the incredible tenacity with which certain ideas have been held despite the fact that they conflicted with the plain experimental evidence, or the neglect of theories that would have quickly solved an experimental puzzle. None of these elements fit in with the conventional model of the scientist; they seem unlikely to yield to rational study; and yet they play a part in scientific work.

He was acutely aware of the overwhelming evidence that all too often, “there is no regular procedure, no logical system of discovery, no simple, continuous development. The process of discovery has been as varied as the temperament of the scientists.” Oftentimes, the chaotic nature in which scientists succeeded and failed was shocking. Some of the most important scientific contributions were built upon bad experiments, incorrect hypotheses, misinterpretations of data, etc. Some simple experiments yielded massive discoveries and some very expensive experiments yielded nothing. An extreme example that Holton cites was John Dalton, whose atomic theory was built on FOUR fundamentally incorrect assumptions but still revolutionized our understanding of the makeup of the chemical world.

A science of progress felt daunting, but Holton believed it was extremely worth doing. He believed that the study of the messy personal context of discoveries could soon come into its own as a full-fledged field. He understood that the basis of a field being the unstructured testimonies of scientists was frightening off investigators rather than attracting them. Nevertheless, he believed this area of scholarship would soon become a central part of scientific studies because it could grow the field of science with its learnings. So, he opted to embrace the mess.

In taking this prescient step, he drew a key distinction. He believed that we should be much more clear in communicating exactly what we mean when we use the term “science.” He writes in the introduction to a book in 1952:

The dilemma is resolved...by distinguishing two very different activities, both denoted by the same word, “science”: the first level of meaning refers to private science (let us term it S₁), the science-in-the-making, with its own vocabulary and modes of progress as suggested by the conditions of discovery. And the second level of meaning refers to the public science (S₂), science-as-an-institution, textbook science, our inherited world of clear concepts and disciplined formulations. S₁ refers to the speculative, creative element, the continual flow of contributions by separate individuals, each working on his own task by his own, usually unexamined methods, motivated in his own way, and uninterested in attending to the long-range philosophical problems of science. S₂, in contrast, is science as the evolving compromise, as the growing network synthesized from these individual contributions by the general acceptance of those ideas which do indeed prove meaningful and useful to generations of scientists. The cold tables of physical and chemical constants, the bare equations in textbooks, for them hard core, the residue distilled from individual triumphs of insight, checked and cross-checked by the multiple testimony of general experience.

He later wrote:

A very different set of rules holds in S₁ than in S₂. I do not doubt that solid knowledge about S₁ can be achieved. A science of S₁ must be possible. Though scientists themselves may for a time frown on such an enterprise, one may take comfort that the best of them—for example Einstein and Bohr, as demonstrated in these pages—would not.

Holton believed that S₂’s strong commitment to statements that can be categorized as 1) empirical matters of fact—which usually boil down to physical measurements—and 2) statements concerning logic and mathematics was a major reason that science had grown so rapidly since the 1600s. Limiting most public scientific statements to these areas helped scientists be sure that they were communicating their hypotheses extremely clearly. This minimized the amount of time spent on dealing with the ambiguity of statements and, instead, let the scientists focus on publicly verifying or falsifying statements. In all, he believes this propensity towards S₂ helped “forge a wonderfully strong and successful profession.”

When philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead said, “Science can find no individual enjoyment in Nature; science can find no aim in Nature; science can find no creativity in Nature,” Holton believed he surely must be referring to the “stable” aspect of science, S₂, and not S₁.

Even the generation of hypotheses, which scientists then use the scientific method to rigorously test, is often quite unscientific. “The process of building up an actual scientific theory requires explicit or implicit decisions, such as the adoption of certain hypotheses and criteria of preselection that are not at all scientifically ‘valid’ in the sense previously given [in the scientific method] and usually accepted.”

A prominent example is that, in the writings and accounts of many great scientists, it is very clear that they saw their scientific explorations as a way to prove the existence of God and find his fingerprints in the natural world. Kepler believed this to an extreme extent, having initially planned to enter the clergy but later becoming a scientist. He believed science was an equally valid path to understanding God’s work. Descartes makes clear in his own formulation of the Law of Conservation of Momentum that the law springs from the invariability of God. Galileo saw the laws of nature as proofs of the Deity equivalent to the Scriptures. Newton once wrote in a letter, “When I wrote my treatise [Principia] about our system, I had an eye upon such principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity; and nothing can rejoice me more than to find it useful for that purpose.” And in each of Einstein’s three great papers of 1905, which are written in quite different areas of physics, the common thread is that each helps fix asymmetries or incongruities of a “predominantly aesthetic nature.” ‘God probably wouldn’t have done it like that,’ was the ethos.

Scientists have since replaced the use of ‘God’ with something like ‘Mother Nature.’ Maybe that hasn’t changed much in the way we go about science. Or, maybe it leaves us much more liable to accept ugly equilibria and asymmetries when we view the creator as a ‘tinkerer’ rather than an ‘intelligent creator.’ Examining the effect of this change on science seems like an excellent question for modern scholars of progress. For now, I hope this passage establishes the importance of S₁ and highlights just how prescient Holton was in publishing these thoughts as early as 1952, almost 70 years before Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison wrote their famous Atlantic article calling for a ‘new science of progress.’

And Holton’s writing went far beyond the mere accounting of historical accidents and anecdotes. He even attempted to model a question that still vexes modern scholars of innovation, “When do ideas become easier to find?”

The model is quite eye-opening.

When do ideas get easier to find?

The apparent decrease in the productivity of scientific research is much talked about by innovation scholars. The most famous piece of scholarship is Bloom et al.’s Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find? which outlines the substantial decline in research productivity across numerous fields in recent decades.

(I briefly go over pieces of the paper in this post and Matt Clancy does a much more thorough job here)

When people hypothesize about what is causing this decline, they tend to credit the so-called ‘burden of knowledge’ as being responsible. The belief is, in essence, that as fields become more and more complicated, it takes longer to become expert in them and harder to discover new ideas in the field. And, when looked at this way, many feel like diminishing returns to research productivity are natural.

But Holton’s models, from 1962, of what assumptions lead to rising vs. falling research productivity make it clear that there are clear steps we can take to try to increase research productivity. We are currently doing the opposite of these steps in many cases. For those who believe that falling research productivity is somewhat ‘inevitable’, I hope this section opens your mind up to the possibility that this problem might have been ‘man-made’ by flawed incentives.

Holton’s “Zeroeth-Order” Approximation

Holton set out to sketch a rough model for the growth of research ideas in science. He knew that the model would not tell us everything about “how science works,” but that it would help explain some of the more marvelous aspects of scientific growth. And, so, he began with a zeroeth-order approximation that he knew to be inadequate from the beginning. But he felt it would be useful to improve upon to attain a more accurate, first-order, approximation later on.

He uses the analogy of a voyage of discovery to describe the research enterprise. On average, a single voyager will expect the number of new islands they discover to increase more or less linearly in proportion to their time spent exploring. The same will be true if there are multiple ships exploring, but not so many that they are in contact with each other or overlap with each other ships’ search patterns. So, the number of unknown islands that remain to be found in a finite ocean—the number of interesting ideas—will be expected to linearly drop off over time because every island that is found is one less island left for another explorer to find.

As more and more islands are found, more voyagers will begin to set off on explorations because interest in these types of explorations will be growing. This increase in participation will guarantee that the decrease in islands left to be found decreases more exponentially than linearly. This exponential decrease in islands left to be found is due not just to the increasing competition, but also due to the increasingly overlapping community of voyagers sharing tips and tricks on how to better find new islands.

Eventually, with the number of explorers growing, the domain knowledge of each explorer ever-increasing, and the number of islands left to be found decreasing, the field will become less attractive and the number of explorers will diminish.

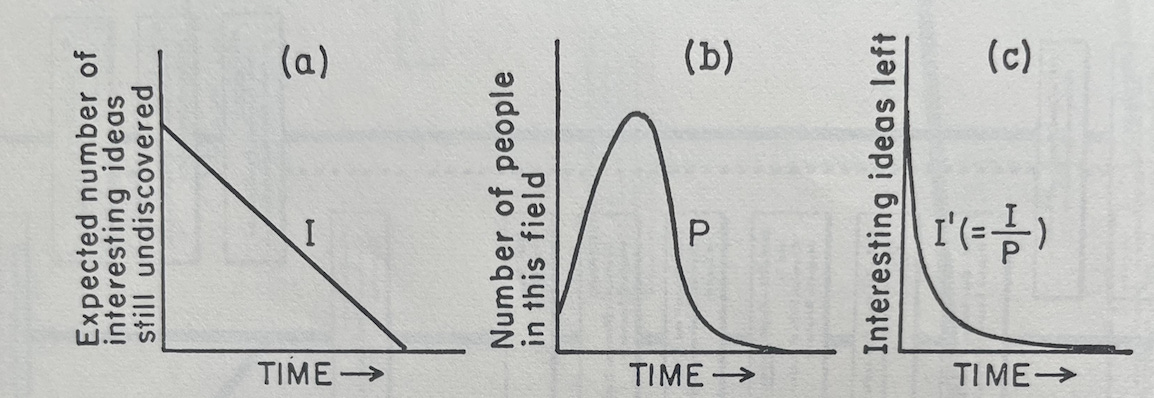

The graphs below visualize pieces of Holton’s zeroeth-order approximation:

(a) Visualizes I: the linear decrease in ideas to be found over time when there are few enough researchers that they are not encroaching on each other’s territory or sharing ideas

(b) Visualizes P: the number of people who crowd into a field as it gets hot and leave as it gets too crowded and the number of ideas left to find diminishes

(c) Visualizes I’: the interesting ideas that are left over time as researchers begin to crowd each other out and share ideas

This approximation obviously does not explain why science as a whole increases its scope over time rather than deteriorating. That will be accounted for in the first-order approximation. Holton writes:

Nevertheless, we already recognize that for some specific and limited fields of science this model is useful. Thus in 1820 Oersted’s discovery of the magnetic field around wires that carry direct current, and the theoretical treatments of the effect by Biot, Savart, and Ampére in the same year, sparked a rapidly rising number of investigations of that effect; but it was not long before interest decreased, and by the time of Maxwell’s treatise (1873) no further fundamental contributions from this direction were being obtained or even sought.

The following graph further applies all of the above ideas into one graph with the addition of curve A, the number of ideas known and applied, which mostly mirrors line I'—which tracks the number of ideas left to discover.2

This concept of a curve A is further developed in the first-order approximation.

This zeroeth-order model makes clear that, under its assumptions, one would expect ideas to get harder to find over time. However, there are some key behaviors it does not account for.

Holton’s First-Order Approximation

Holton goes on to build a first-order approximation to model the growth of scientific ideas, iterating on the model above. He wanted this first-order approximation to account for how research ideas and fields grow and branch off of one another, which the zeroeth-order model did not account for.

Examples of this key behavior include two figures he shared which will most likely be illegible to the reader, but should still give you a sense of the expansion and branching he was talking about. The first graphic attempts to show how just a small subset of fields in math, physics, chemistry, and aerodynamics arose from more general lines of research in the early 1900s.

The graphic is obviously far from exhaustive, but it should paint a pretty clear picture of how fields of science organically develop from each other’s explorations.

He then goes on to paint a much more fine-grained picture of this phenomenon by showing the massive branching out of new fields of physics related to molecular beams, magnetic resonance, and other work that was spawned by I. I. Rabi’s work in developing the original molecular beam techniques—represented by the black box at the bottom which begins to branch upwards—and stimulating a group of productive colleagues and students to explore these problems further.

Just some of the names in those tiny boxes include key work by the likes of:

Niels Bohr

Richard Feynman

Freeman Dyson

Shinichiro Tomonaga

Julian Schwinger

Otto Hahn

Emilio Segré

Otto Frisch

Eugene Wigner

While this expansive tree is a case of science growing at an ideal rate, the reader can picture the more modest branching that a modest tree would exhibit as well. It was this fundamental, branching aspect of science that Holton set out to incorporate into his first-order model.

He begins with Figure A, where the curve D, the number of basic ideas published in an area, is simply the mirror of the curve I', the number of ideas left in a field to be published. This image should be familiar from the above zeroeth-order approximation.

Holton then extends on this concept of a single, independent curve D with a decreasing slope. Instead, he begins to explain how D can be the starting point for a branching process of discovery.

The beginning of curve D indicates necessarily the occasion that launched the expeditions in this field, say the discovery in 1934 of artificial radioactivity by Joliot-Curies while they were studying the effect of alpha particles from polonium on the nuclei of light elements.

Up to this point their research had followed an older line, originating in Rutherford’s observation in 1919 of the transmutation of nitrogen nuclei during alpha-particle bombardment. The new Joliot-Curie observation, however, inaugurated a brilliant new branch of discovery. We suddenly see that the previous model [the zeroeth-order approximation] was fatally incomplete because it postulated an exhaustible fund of ideas, a limited ocean with a definite number of islands. On further exploration, we now note that an island may turn out to be a peninsula connected to a larger land mass. Thus in 1895 Röntgen seemed to have exhausted all the major aspects of X-rays, but in 1912 the discovery of X-ray diffraction in crystals by von Laue, Friedrich, and Knipping transformed two separate fields, those of X-rays and of crystollography. Moseley in 1913 made another qualitative change by showing where to look for the explanation of X-ray spectra in terms of atomic structure, and so forth. Similarly, the Joliot-Curie findings gave rise to work that had one branching point with Fermi, another with Hahn and Strassmann. Each major line of research given by line D in Figure A [below] is really a part of a series D₁, D₂, D₃, etc. as in Figure B. Thus the growth of scientific research proceeds by the escalation of knowledge—or perhaps rather new areas of ignorance—instead of by mere accumulation.

Holton goes on to explain that when an important insight or some chance discovery causes some new branch line, D₂, to be created and branch off, fruitful research does still continue on the old branch line, D₁. But many researchers, including an inordinate number of the more original ones, will transfer to D₂. And in this new branch they will apply their original minds as well as whatever applicable experience they acquired working on D₁.

These new, exciting branches often tend to experience inordinate growth, draw a disproportionate number of graduate students, and, hopefully, this group will continue to make discoveries that create further new branches that they or their graduate students can transfer to.

And, to prove this is not all theoretical, Holton shares a graph showing the exponential growth in the energy of particle accelerators in the mid-1900s, along with the branches of research underlying this growth. Each of these technologies, from DC generators through proton synchrotrons, contributed to this constant exponential growth that was entirely the result of the continual branching of curves D₂, D₃, etc.

Particle accelerators are a case of research in which, aided by groups of researchers both sharing information but also working in locations some distance from one another, researchers were able to do more than march along building on each others’ insights, they were able to leapfrog each other.

One research team will be busy elaborating and implementing an idea—usually that of one member of the group, as was the case with each of the early accelerators—and then will work to exploit it fully. This is likely to take from two to five years. In the meantime, another group can look, so to speak, over the heads of the first, who are bent to their task, and see beyond them an opportunity for its own activity. Building on what is already known from the yet incompletely exploited work of the first group, the second hurdles the first and establishes itself in new territory.

Holton was writing this at the end of a bit of a golden-age of basic research where many new areas had been spawned and experienced explosive growth and branching. Accelerators were not a particularly unique case of explosive scientific productivity at the time. What was unique about accelerators was that progress was easy to measure and the data were readily available. He saw this first-order model as a qualitative one that effectively modeled the growth in the depth of knowledge of many types of theoretical and experimental ideas that resisted quantification. Particle accelerators were simply a case where the ‘depth of knowledge’ lent itself to easy quantification.

Another interesting detail to take note of is just how quickly the rate of progress curtailed for most of the individual accelerator branches in the graphic above. And there’s a lesson to be learned here: the slowing rate of progress for the individual curves did not matter much at all. While it was all too common for a single branch to rapidly curtail in research productivity, almost all new branches had explosive growth in their early stages. So, as long as new branches were being created frequently, growth was explosive.

Holton did point out that the single assumption that was vital in making his first-order approximation more accurate than his zeroeth-order approximation was that researchers were willing and able to learn from each others’ research from various areas and begin building off of it. To him, that was how branch-making thrived.

At the time, teams of interdisciplinary basic researchers were one vital way of enabling this ongoing learning process across fields. He may have taken for granted that this would obviously be the direction in which science would continue to go. It’s easy to see why. He was writing in the aftermath of the smashing success of large labs and projects that married physicists, chemists, mathematicians, electronics engineers, and many others into the same spaces and on the same teams. These labs and projects included the Cavendish Laboratory, E.O. Lawrence’s lab at Berkeley, the Manhattan Project, the MIT Rad Lab, the Harvard Radar Countermeasures Laboratory, and others. Even when these researchers didn’t publish together, they would work closely together day-to-day and discuss each other’s problems. These new branches continually came from the greats in their respective fields working on and discussing the problems of other fields with great researchers from that field. To get a clear idea of just how prolific these combinations could be in spawning new branches, please visit my John von Neumann piece to experience just how many branches one great mind could create working in this way.

And, if two fields felt too far apart for a pair of researchers to understand each other, the presence—and often friendship— of researchers from intermediate fields usually smoothed this process. As Holton writes:

While an applied organic chemist, say, and a pure mathematician, by themselves, may not understand each other or find anything of common interest, the addition of several physicists and engineers to this group increases the effectiveness of both chemist and mathematician, if each scientist is sufficiently interested in learned something new.

Holton later even goes on to state that, with the constant branching off of one subject, such as mathematics, to a separate subject, such as physics or chemistry, that, “It is becoming increasingly more evident that departmental barriers are going to be difficult to defend.”

Exactly the opposite happened.

We built silos, not branches

Much has been made in the progress studies community on the problem of ‘good ideas becoming harder to find.’ And, while we can’t be sure that the ‘burden of knowledge’ isn’t responsible for this, it seems quite likely that this problem might be man-made. Holton, initially publishing this model in 1962, was writing at the end of a decades-long run that is seen as a scientific golden-age for qualitative reasons, like the birth and development of fields like relativity and quantum mechanics, and for quantitative reasons, looking at metrics such as TFP growth.

In that era, there was a distinct feeling that ideas were getting easier to find. So, why does it feel like we’ve reverted to Holton’s zeroeth-order world rather than continuing to live in his first-order world?

In short, it seems that there is less and less incentive for researchers to do the kind of research that creates new branches. And, if the possibility for a new branch to be fleshed out does arise, the incentives are not there for a researcher to jump ship and help develop this new area of research. And, without a critical mass of researchers, a branch never really takes off at all.

Looking at just a few pieces of the modern innovation literature paints a pretty clear picture of how the opposite of what Holton hoped for has become a reality.

The Pivot Penalty

Firstly, Hill et al. point out that, since the 1970s, it has gotten riskier and risker to pivot further and further from your main area of publishing. Your likelihood of becoming highly cited after a major pivot is less than half as likely today than it was in the 1970s. The negative slopes of the lines below indicate that you are less likely to write a highly cited paper the larger your pivot is.

And, while it’s unclear if the slope of a line from, say, the 1950s would be positive, meaning that researchers would be more likely to become highly cited if they made a major pivot in their research instead of a small one, it anecdotally feels very clear that the 1950s line would at least have a less negative slope than the 1970s line. The probability of a researcher winning a Nobel in a different field than the department they worked in or having the ability to gain tenure in multiple different types of departments has likely been going down since at least the 1970s.

Furthermore, Hill et al.’s analysis of research pivots and Covid-19 research showed that:

Younger, less established researchers were less likely to make a large pivot to Covid-19 research and

Those who relied on grants for research funding were increasingly less likely to be able to make a large pivot to Covid-19 research

The first point is particularly troubling because, as Holton pointed out, younger researchers joining a new branch of research was particularly important to help a new branch begin to flourish. In addition, younger researchers often depend on grants and are less likely to be sitting on the piles of extra research funds that seem to enable pivots like this.

Novelty doesn’t get you tenure

Wang et al. look at the novelty of scientific papers and their likelihood of becoming a top 1% cited paper written in their field. And, in an exciting turn of events, highly novel papers are far more likely to become blockbuster papers, rewarding the researchers for their risk!

But there’s a problem. It takes years for those citations to accumulate and for your paper to become appreciated. Like, enough years that your tenure vote may come and go without the paper being appreciated. At the 3 year mark, you may still have about the same number of citations as the completely non-novel research on average, possibly less.

Not to mention, when your day finally does come, the influx of citations often comes from a foreign field and not your own. So, not only will you need to wait up to 15 years for the sun to shine on your innovative work, but your recognition will possibly come from researchers who don’t even work in the same building as you do.

If academics are often incentivized to seek tenure and recognition from their peers, then this is not good news. Even if you are happy to receive the warm and fuzzy praise from people in a different department 15 years down the road, it’s not the kind of praise that you can trade in for a higher salary from a department in your field in many cases.

Furthermore, Bhattacharya and Packalen construct a model that demonstrates just how devastating the emphasis on citations and h-index can be in disincentivizing real scientific exploration. Because, while citations are one important metric in science, actual scientific progress depends on a steady flow of exploratory tinkering and new ideas. New ideas are risky to work on because, in the beginning, it is difficult to distinguish between ideas that could become a great branch one day and complete duds. And this base of exploration, this tinkering around, is what real breakthrough discoveries, branches that then spawn extremely productive second-order branches such as Rabi’s crystallography work did above, often depend upon. And, since citation-based metrics and decisions make little effort to distinguish between this exploratory work and incremental work on well-established research areas, all incentives steer rational researchers to got to “hot”, well-developed areas where well-done incremental work can garner high numbers of citations. All of this renders science less vibrant.

This is especially problematic if you subscribe to Holton’s view that it often takes a great mind to “turn to his full advantage the illogical and unexpected.” These words, written in reference to John Dalton’s atomic theory coming out of four completely incorrect assumptions, could possibly apply to any scientist engaging in exploratory work that attempts to create vibrant branches. If these great minds are also the minds that can reliably generate high-citation counts doing incremental work in “hot” areas, then all of science is losing out on their true potential.

Of course, it’s hard to do new research on an older branch!

If more and more researchers are working further along fewer branches of knowledge, then of course ideas are getting harder to find! That’s exactly what you’d expect. Our current equilibrium could be understood as something not dissimilar to the point in Holton’s zeroeth-order model when the number of researchers is peaking but a large proportion of the good ideas have been found already. Of course, the truth is likely somewhere in the middle of these two models because we do still discover some branches. But it does seem clear that the current state of things should be classified as far closer to Holton’s zeroeth-order model than science was at the time of his writing.

Being so much closer to the zeroeth-order approximation, it’s no wonder that average ship captains are getting older and older and the size of the team it’s taking to find an island is getting larger and larger. It’s important to remember that some new branch, D₂, only partially builds off of its parent branch, D₁. So, while experience working on D₁ is helpful in making discoveries on D₂, much of the knowledge on D₁ is not helpful at all. So, for researchers on D₂, some creativity and an eagerness to explore is far more important to making discoveries on D₂ than esoteric bits of knowledge about D₁. But, if all the scientists are crowded on D₁, then it’s clear to see how time in the field may outweigh creativity more so than it would on a new branch.

This, also, is not simply theoretical. At the time of writing, in 1962, Holton cited work by M.M. Kessler which found that 50% of the references cited in research papers published in the Physical Review, the top physics journal at the time, were less than three years old. And only 20% were more than seven years old. Decades on from the paradigm-changing discoveries of relativity and quantum mechanics, physics researchers had still been rapidly creating new branches of research and leapfrogging each other in the race for human progress, constantly citing younger and younger papers and letters. Science was moving so fast that a non-negligible number of citations in the journals were citing personal correspondence and conversations with other physicists as opposed to published papers.

Holton believed that we might see the end of departmental barriers and a system that evolved to incentivize these all-important branch creations. And he has lived through just the opposite.

Obvious Advice

If you buy into the model described here, it seems the single greatest thing a new science organization could do, even if it’s at the expense of ALL other things, is facilitate the creation and early development of new branches of science. These branches, when they are discovered, tend to experience periods of explosive growth, have a high likelihood of spawning other new branches, and these new branches are also likely to do the same. Without these new branches, good ideas WILL get harder to find.

Much of what this looks like is likely quite self-explanatory from the rest of this post. But, if you’re looking for some kind of bulleted list. Activities that empower researchers to create branches would include:

Put your researchers from diverse fields in the same place and give them incentives to talk with each other, explain things to each other, and work on things with each other that don’t look like anything going on in their individual fields.

Give them incentives to play (scientifically). Watching Real Housewives might not be a good use of lab time (maybe it is?), but fiddling with interdisciplinary ideas only loosely related to their current work should be okay. The researchers should be viewed not individually, but more as a portfolio. You want some new branch to come out of every X number of researchers, but you shouldn’t require proof that each individual is making linear progress towards this goal. Many researchers might have no progress to show for it, and that’s ok. Similar to working in VC investing, it’s about the hits.

A good rule of thumb might be: be the place that gets the most out of the odd, eccentric, exploratory minds that feel like academia is no longer a great place for them the way it used to be in the era leading up to Holton’s writing. This will likely help you recruit the researchers best-suited to creating more branches AND get the most out of them. MIT and Bell Labs both understood that this was the way to get the best out of a mind like Claude Shannon.

Not to belabor the point, but Vannevar Bush even made a concerted effort to push Shannon to work on genetics problems for a period of time, when Shannon finished his work assisting Bush’s Differential Analyzer project, not because he saw Shannon as a career geneticist, but because he saw him as the kind of playful mind who appreciated new problems and who could do branch-creating work on many of them.

Sometimes, science should feel like play. In the time since Holton’s writing, we seem to have forgotten that.

If you’d like to know more about what Shannon’s path looked like qualitatively and how to foster more of him: Read Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman’s fantastic biography of him, A Mind at Play.3

If you’d like to know more about what a career of creating less ridiculously-novel, but still quite novel branches in insane amounts looks like: Read my piece on John Von Neumann and what his career can teach us about how to generate more discoveries like his.

And, lastly, if you’d like to talk to me about any of these ideas: just DM me on Twitter at eric_is_weird

Hope you enjoyed. Please, if you know anyone who could make use of this post, send it their way! We need more room for exploration in this all-too-boring world. I’m hoping one of these new science orgs having a little fun is a way to make that happen!

Citation:

Gilliam, Eric. “When do ideas get easier to find?” FreakTakes Substack. 2022. https://freaktakes.substack.com/p/when-do-ideas-get-easier-to-find

Holton, Gerald. Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought: Kepler to Einstein. Harvard University Press, 1973.

Notes on the zeroeth-order model: Holton estimated T to be about 5 to 15 years in the frontiers of physical science, which is remarkably close to the robust modern empirical estimates that estimate that it takes about 17 to 20 years for a discovery to become widely applied. Also, he acknowledged that the number of applied researchers might still rise even as basic research participation falls.

Amazon Affiliate link

You may enjoy 3 slim volumes by Nicholas Rescher

The Limits of Science (1984, 1999) (references Gerald Holton)

Nature and Understanding (2000)

Epistemetrics (2006)

Really interesting, thanks for writing!